In one week my three-month sabbatical will come to an end. As I prepare to return, I feel the mounting pressure to hit the ground running, to return more energized and focused, resilient and committed, productive and effective. The congregation’s investment into me should pay off with dividends. I recognize these thoughts for what they are: a warning light for my soul, a danger sign for the congregation, an indicator of our collective illness and idolatry. I am grabbing for control again.

Turning 50, sending our youngest off to college, and inaugurating a new empty nest season in our marriage of 26 years, my three-month sabbatical of travel and rest has included some weighty life transitions. Inevitable and uncontrollable change and letting go, ironically, has also coincided with the release of our co-written book, A Pilgrimage Into Letting Go. Andy and I wrote this book over two years ago, after walking together for a week with our teenagers through the borderlands of England and Scotland. As we walked the pilgrim path of an ancient saint and visited holy sites where the God of Israel has been worshiped by Christians for 1500 years, alongside kids that we suddenly recognized as barreling toward adulthood, we experienced a shift in our spirits around parenting and pastoring. With each step, the Holy Spirit gently pried off our tightly grasped fingers and whispered the invitation to inhabit a different way of being with those entrusted to us. Now these lessons are coming back to meet me again.

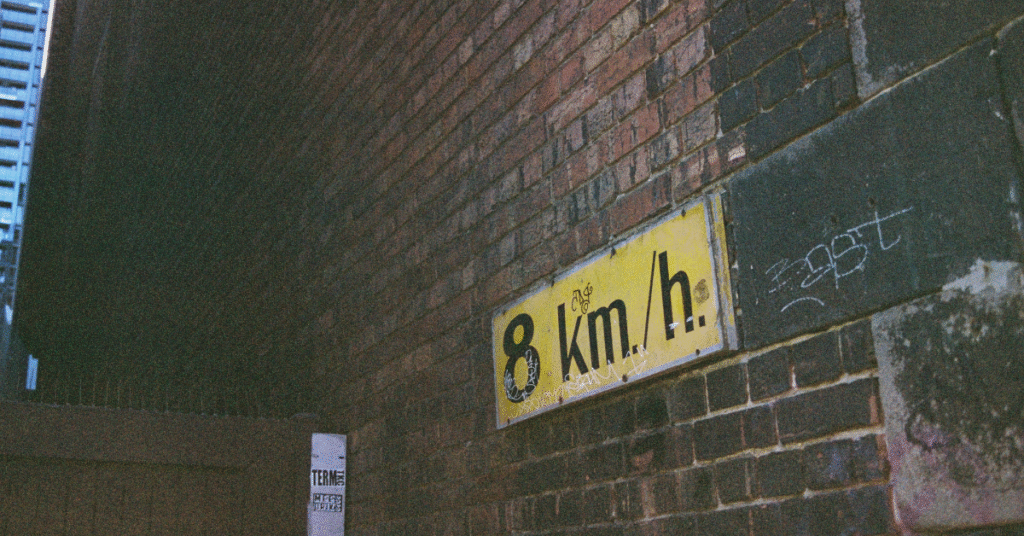

I’m reminded that moving at the speed of our feet, accompanied by the One whom theologian Kosuke Koyama calls a “three-mile-an-hour God,” we could feel in our bodies both that the story holding us is vast and deep, and that our time on this planet is precious and fleeting. How much of it do we spend trying to control how it all unfolds? A futile task at best, damaging at worst. Away from the urgent stream of anxious, foreboding digital content, quietly present to the story of the church’s endurance and mission over time in a different place, we were chastised. How much hubris must we have to think the future of the church is in any of our hands? Is the church of Jesus Christ ours to shape, control, and direct? We are participants in a mystery, both recipients of a gift, and given, ourselves, to the world. What if faithful leadership—in the church and in our own family—looks less like relentless managing and directing, and more like practicing an openness and availability to encountering God and each other in ways that can’t be programmed or controlled?

Sociologist Hartmut Rosa explains that we modern people are moving so fast under so much pressure that we meet the world and those around us as points of aggression – conflicts to wage, problems to solve, tasks to complete, lists to check off, goals to accomplish. We’re pushed to maximize our potential, optimize our actions, and instrumentalize our relationships, pursuing unending increase without pause or completion. The great parent, the excellent pastor, the ideal congregation – it is only good if it is always getting better. If we’re not improving, we’re declining. And if we’re declining, we’re doomed. Growth is our god.

But into this anxious and relentless acceleration breaks these beautiful, unforced experiences of engagement that Rosa calls resonance. Suddenly, we hear the world speaking to us. We sense our underlying, unbreakable connection to all others. We’re summoned by something beyond ourselves, we feel our selves answer back in some way, and we’re changed by the uncontrollable encounter. A moment of eye contact when you are seen and see another truly, holding someone while they’re sobbing, being snapped into focus by the power of the pounding waves at your feet, or helplessly swept up in the soprano’s soaring aria. In our most profound and elemental human moments, we are awakened to life.

These experiences of beauty, wonder, love, awe, belonging or aliveness can’t be forced, and they can’t be captured. We know they happen, and deep down we may even know we can’t make them happen, but that doesn’t stop us from trying. Consider the family vacation that will make great memories, or the worship service that will move and inspire people. Especially those of us entrusted with the care of souls and the shaping of people and communities: we will try to control what is fundamentally uncontrollable. We will breathe life into dust and wonder why it just scatters, dry, between our fingers.

The tragedy is that we grab for control with the best of intentions and end up squashing the possibility of resonance occurring. Deeply desiring that our kids feel love, gratitude or insight, we strive to pour these things into them. We try to prevent loss and pain and buffer them from suffering, turning their lives into projects instead of being with them as people. Faced with the mysteries of a transcendent God, the stories of sacred scriptures, the rituals of enduring worship, and the nuances of complex relationships, we long for our people to be moved, awakened, transformed. So, we strive to make the Christian life visible, manageable, accessible and useful. We tie it up and hand it over, packaged pretty and user-friendly. Then we wonder why God seems unreal, scripture irrelevant, worship flat, and people disconnected. We’re mystified as to why nothing is speaking to us. So, we just try harder, and exert more control, and come up more tired. And after five or seven years, we might get a sabbatical.

But resonance happens, says the sociologist. God speaks, says our scriptures. This world is alive and beloved, says our Creator. Those of us whose lives are shaped by Christ Jesus are drawn by the Holy Spirit into a vast, eternal community, and called into the redemptive purposes of a living, active God. We participate in a story not dictated by us, or even dependent on us, unfolding despite us but also involving us. All that matters most can’t be achieved, only received. We learn to listen to God alongside those entrusted to our care – our congregations and our children.

As parents and pastors, the great temptation is to slip into performing our role, instead of being a person with other persons. Eugene Peterson writes, in his “letter to a young pastor,” “The daily, inescapable reality is that in neither of these areas, worship or family, are we in complete control. If we try too hard, we end up being self-conscious, substituting our ego and performance and reputation for the very thing we are committed to doing.” (The Pastor, 316) Our call as pastors, and as parents, is not to grow the church or propel our kids into the future. It’s not even to be a better pastor or parent. Our call is to walk alongside these beloveds at the slow speed of the human soul with the incarnate Christ, being with and for each other, anticipating encounters we can’t make happen, and learning together to respond to the Spirit’s promptings.

When I return next week to my congregation, I don’t know what reunion will bring, and that is a little bit scary. I do know that when fear and anxiety bubble up, so does the craving for control. But it’s God’s church, not mine. And I know how to begin. It’s how I began as pastor in this little congregation 17 years ago, what I did after the pandemic lockdown let up, and how I’ve eased back in after each prior sabbatical: I will have coffee with every person who will meet with me. No agenda, just listening. Listening to them, listening with them to the Spirit’s movement in their lives, and listening together for what God might be saying to us. We may hear something and we may not, but we will practice listening and being available. And when God does speak, we are ready to respond.