Do you have a story of a time when a pastor — maybe even you — tried to shock the congregation, but went too far? The challenge for pastors is that “too far” is in the eye of the beholder. As Jesus taught time and again, one person’s scandal is another person’s holy justice. I was very glad to meet Suzanna Krivulskaya at a writing workshop this summer, and it’s an honor to present her post below. What a marvelous, shocking, and compelling story of a time when a pastor went very far — but not too far — to raise funds for justice.

Yours truly,

Adam Copeland, Center for Stewardship Leaders

Unholy Sundays

Suzanna Krivulskaya

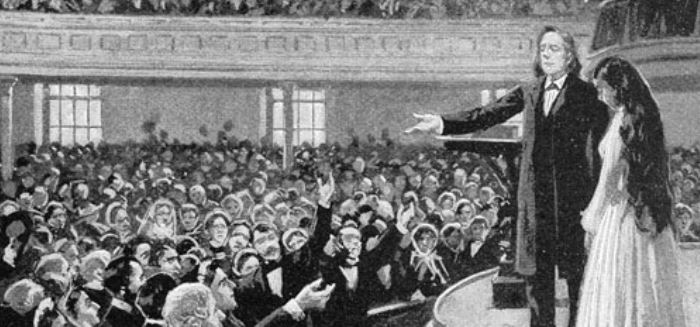

The most famous abolitionist pastor of the nineteenth century sometimes used his pulpit to auction off slaves. Granted, Henry Ward Beecher didn’t do it for profit; he auctioneered to secure the slaves’ freedom.

The first time caught the Brooklyn Plymouth congregation by surprise. On a pleasant June morning in 1856, Beecher concluded his Sunday sermon with a reading from the gospel of Luke. In the passage, Jesus responds to criticisms of healing on holy days: “Is it lawful on the Sabbath days to do good, or to do evil? to save life or destroy it?”

With that, Plymouth Church members expected to sing the closing hymn and be dismissed after the benediction, but their pastor had other plans for the afternoon.

Beecher explained that he had been contacted by a slave trader in Richmond about a young woman. Sarah, a mixed-race slave, was on the market after her own father traded her in for cash. A product of sexual assault on another enslaved black body, Sarah had made her father $1,200 richer.

The story was so tragic (though not unusual) that the Virginian slave trader now in possession of Sarah reached out to Beecher: would the minister help buy her freedom?

Beecher agreed to try, but demanded that Sarah come North, with a promise to return back to the South should her freedom not be paid off in full.

Some of the money, the pastor explained, had already been raised. But the rest was up to the congregation of Plymouth Church. Would they do good on a Sabbath? Would they set the slave free?

“Come up here, Sarah, and let us all see you,” Beecher said, as Sarah meekly ascended the steps to the podium.

“Look,” Beecher said facetiously, “at this remarkable commodity — human flesh and blood, like yourselves.”

“Who bids?” he pleaded.

Beecher’s auction block strategy proved successful. With gasps and tears, parishioners rose up to contribute to the offering. Those who had no cash on them (mostly women) took off their jewelry and threw it in the collection baskets. Finally, with $783 in cash plus some precious stones and metals, not only could Beecher secure Sarah’s freedom, but also that of her two-year-old son.

When the total sum was announced, the congregation erupted in celebratory applause. Beecher allowed them to cheer on, but noted that, save this joyous occasion, he disapproved of “an unholy clapping in the house of God.”

I wonder if today’s churches would benefit from more “unholy” activity on Sunday mornings. We might disagree with Beecher’s methods or question his strategy, but transforming the pulpit into an auction block had one indisputable effect: it shook the wealthy, well-meaning, white Brooklynites out of their complacency.

Sarah’s presence in the sanctuary made tangible the horrors of slavery. Seeing her body in the flesh made other bodies discard their adornments — rings, necklaces, cufflinks, and lockets — and put them to better use. Sarah was free at last. And, with less stuff weighing them down, the congregants, too, finally felt free to start clapping in church.

More Information

Suzanna Krivulskaya is a graduate student in history at the University of Notre Dame. She is writing a dissertation on religion and scandal in America.