I felt like a 6-year-old on Christmas morning, waiting in anticipation to begin the morning ritual of ripping through glittering paper. But it wasn’t Christmas morning, it was my first day of Bible College. I was 23 years old, sitting on a cold, plastic orange chair from the 70s, and waiting for my theology class to start, positively giddy. The professor began and I could hardly contain the smile that stretched from one ear to the other. I was finally getting to learn about God and the Bible the way I’d always wanted to. Glittering wrapping paper had morphed into Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology and I was ready to tear into it.

Over my three years of Bible College, I took nothing but systematic theology. Grudem’s definition of systematic theology is “collecting and understanding all the relevant passages in the Bible on various topics and then summarizing their teachings clearly so that we know what to believe about each topic.” This precise (but limiting) definition guided the way I studied theology in those years.

I took courses in Christology: the study of Christ; soteriology: the study of salvation; and bibliology: the study of the Bible. You name it, I took it, memorized it, tested on it, and wrote paper after paper on it. I read so much I needed reading glasses to ward off the migraines I started experiencing. To say it was intense is an understatement, but I loved each course as much as the next. Then the red flags slowly began to appear.

It was in my Bible Studies Method class that I first heard warnings about only studying God in this manner. Professor Ray Lubeck said Systematic Theology and Bible Study Methods can be a lot like dissecting a frog in science class. It may be important to understand all the working parts, but if we begin to see the word of God as lifeless, we are in deep trouble. Yet, how can one study the Bible so intensely without it losing some life? Without it becoming simply a set of memorized tenets? It can be difficult, because this method of study doesn’t always leave much room for mystery. When you are required to know so much, it can be hard to admit that, in fact, we know very little.

———————————————-

After my graduation in 2006, I found this lack of mystery leading me into a season of unlearning, and all the knowledge I had gained about who I thought God was slowly began to slip away. Learning theology in this manner certainly offers interesting information about the Bible and God, but it doesn’t always translate well into our lived experiences. If we’re paying attention, our lives are asking questions that our definitive theological tenets often fall short of answering. And our attention, unfortunately, becomes keenly focused when suffering enters the picture.

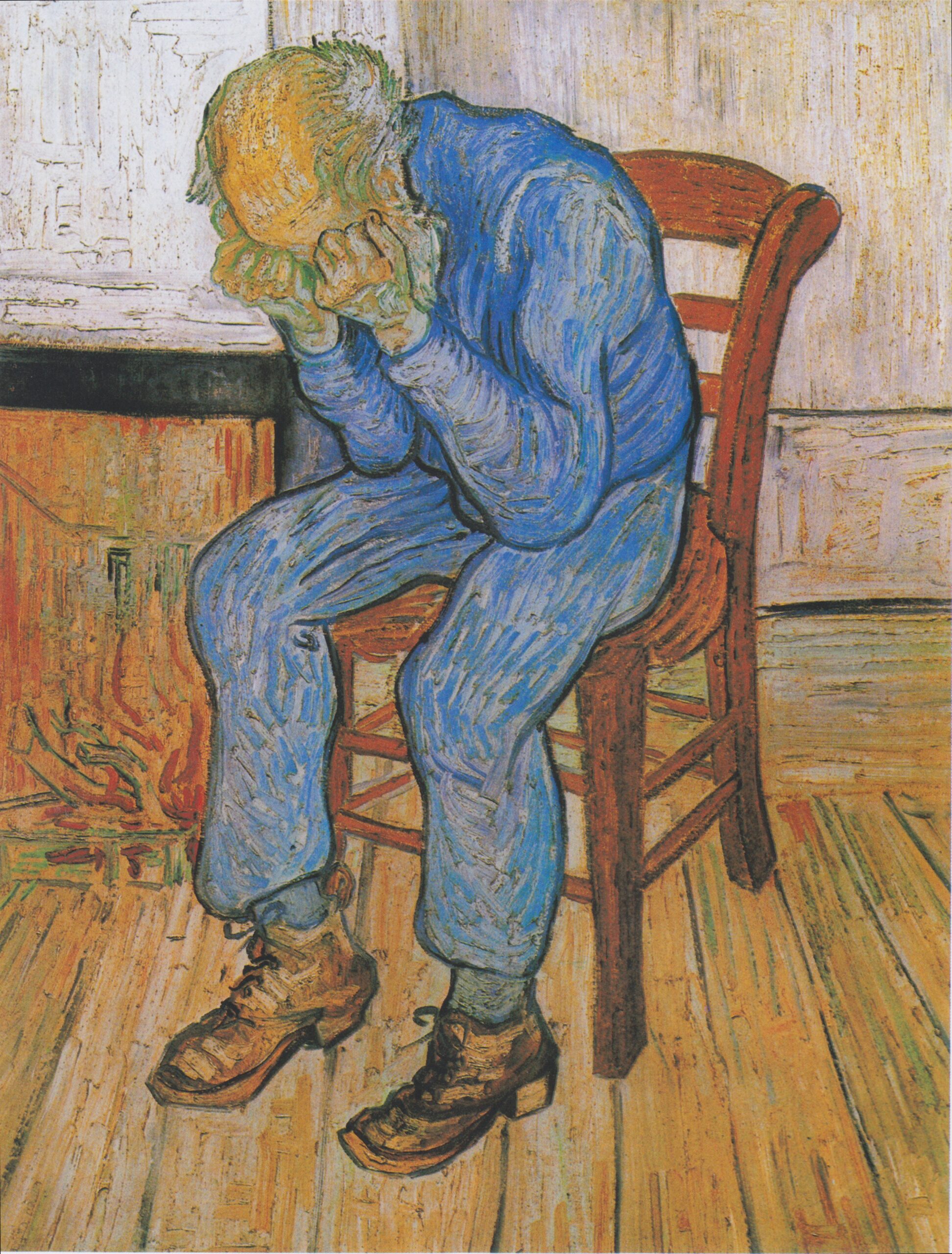

[Vincent Van Gogh, Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity’s Gate), 1890]

Over the last ten years, my husband and I have experienced being fired as youth pastors, my sister suddenly passing away, and struggles with infertility. I tried my best to hold onto the knowledge I had but these experiences eventually led me away from doctrinal tenets to sitting on a pile of ash. Can inerrancy help us grieve the loss of a loved one? Does doctrine on the humanity of Christ alleviate suffering? It didn’t for me and in fact, the more knowledge I had, the more reasons I had to be angry with God. The questions spewed from me like a cracked pipe in an old basement: If God is almighty why doesn’t he heal me? If God is love, why then do I feel his distance more than this presence?

Christian culture didn’t help answer these questions any better. Instead, the message I received was that I needed more faith or that God was testing me. None of the knowledge (nor the platitudes) brought comfort. They only made me angrier and ashamed of my anger. But I truly couldn’t reason or pray my way out of the grief. For years, I felt like I was asking for bread and God was giving me stones! (Matthew 7:9) It wasn’t until I relinquished my grip on what I “knew” about God and embraced what I didn’t that finally brought relief.

I experienced a few fleeting moments of wonder at Bible College. In my Christology class, I remember attempting to understand Jesus being both God and man, and just couldn’t do it. The wonder was visceral as my mind shut down and I happened into a moment of complete awe. Another time was after reading the chapter “God Incomprehensible” from Knowledge of The Holy by A.W. Tozer. The moment of awe was so immense, I fell prostrate to the dormitory floor for what seemed an eternity. Yet, as soon as these moments ended, off to class I went to memorize the “concrete” things of God. Despite their ephemeral nature, I’ve held onto these moments more than any doctrinal statement and they have served as a blueprint of wonder.

———————————————-

Nicolaus of Cusa was one of the most important German thinkers and ecumenical reformers of the 15th century. His lifelong pursuit was to reform and unite the universal church with the Roman Catholic church. One of his known writings was a book on learned ignorance. Essentially, he addressed three stages of knowing: those who don’t know that they don’t know, those who don’t know but think they ought to know, and those who embrace unknowing as part of the human experience.

[Nicholas of Cusa in the Schedel chronicle]

I am sure many people are familiar with unknowing but are often stuck in stage two, believing they ought to know what they don’t know. This was me for years after Bible College, spinning my theological wheels and demanding to know the reasons behind my suffering as if more knowledge of God would alleviate the pain. But answers don’t bring comfort. What we want is to not be in pain anymore, to know our suffering will end, but even the knowledge of heaven and of a new earth to come doesn’t bring the comfort we need in acute moments of pain. This is a stage Niculous of Cusa tells us we all must journey through in order to lay down our “oughts” and embrace mystery.

I am now in my forties and the hardest question I’ve had to let go of is why? in order to remain steadfast in my faith. I have witnessed friend after friend walk away from God because their “oughts” and “whys” became their guide, believing they had a right to know more about God than humanly possible.

This was Job’s biggest mistake, the demand of God to answer him for his suffering, yet God didn’t answer. Instead, God reminded him of the great mysteries of the earth and of the heavens, of the animals and seasons. You would think this was a distant and cruel response to Job’s suffering, but there is grace in mystery if we are willing to lay down our demands for knowledge, in essence, our desire to “become like God, knowing good and evil.”

This is what tripped up humanity in the beginning and it’s still getting us today. We ignore the garden, planted for us, to sustain and nourish us and trade it for knowledge. Some things are best left on the tree.

When we are able to embrace a learned ignorance and lean into the mystery of God, we may not find the instant comfort we crave but we will find community. A God who suffers with us, and others who will sit with us on our pile of ashes. If we are to make any radical changes in this world, we must first embrace the human condition, igniting compassion that will embrace the poor and the outcast.

The Gospel is a message of grace and mystery. We cannot have one without the other. If our theological efforts attempt to eliminate mystery, or sidestep suffering, we will only add to our suffering and the suffering of others. But if we learn to accept our ignorance, we will learn to accept our humanity, and through that, we will be able to embrace the whole of this world as it is, and not as we think it ought to be.

Beautiful…… Amen and Amen ❤️