I worship in a denomination that emphasizes the saints. If you’ve visited an Orthodox church of any stripe (Russian, Greek, Ethiopian, etc.), you might have experienced a bit of sensory overwhelm as you entered the building – the smell of incense, the drone of the choir, the flurry of giggling, squabbling children pushing past your knees (because who needs Sunday school – or seats, for that matter?), and everywhere the colorful yet austere icons of Christ, Mary, and the saints, framed by flower wreaths and illuminated by rows of quickly liquifying candles.

I’m still relatively new to the Orthodox tradition, and the novelty of its trappings hasn’t quite worn off. I’m not sure it ever will, but I’ve found an unlikely spiritual home in the scent of melting beeswax, the concept of theosis, and the company of a loving community – which includes, my priest assures his most skeptical parishioner, those long-dead saints.

So I tentatively bought a book to start introducing my own daughters to the stories of those saints. Unsurprisingly, it’s rife with bloody martyrdom and fantastical miracles, but I’ve enjoyed many of the more unexpected details within its pages. Some of my favorite characters include:

- St. Mary of Egypt, a prostitute turned desert-wandering ascetic who walked on water without so much as a blink, and whose grave was dug “with the help of a passing lion.”

- St. Herman of Alaska, who served the Aleut people and loved to bake cookies for the children in his community.

- St. Marina, who successfully fought off the devil with the aid of a giant hammer.

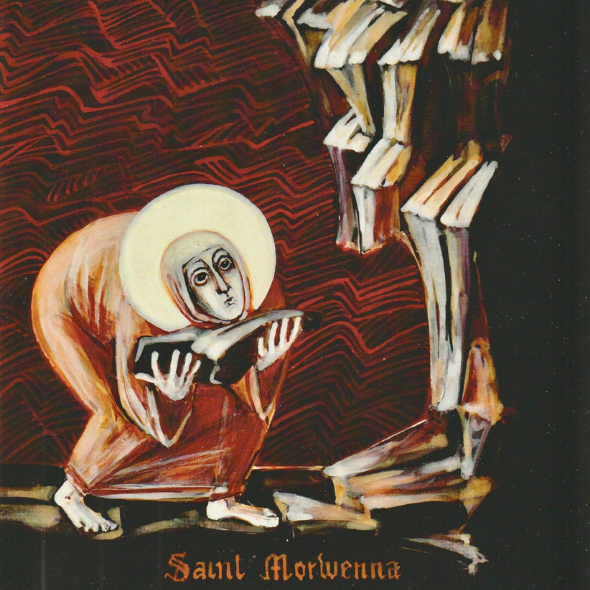

- St. Morwenna, who didn’t do much of interest besides build a church on a forbidding crag in Cornwall, slowly and diligently carrying one rock up the slope at a time with her own two hands.

What the heck makes someone a saint, anyway? Is it the mighty swing of the hammer, or the faithful patience of bearing stone after stone? The ascetic wanderings and miracles, or the cookies?

—

Recently, I decided to take a walk down memory lane by scrolling through my old Instagram posts. A fuzzy, lifted-from-Google image of a smiling Robin Williams in rainbow suspenders caught my eye. I’d forgotten I’d written this:

I met a woman in an elevator once who hugged me in tears. She’d just learned that Leonard Cohen had died. I rolled my eyes a bit (it’s not like you knew him, duh), but my more emotionally intelligent husband had a heartfelt, consoling chat with her. Also, I was a big fat hypocrite.

I didn’t know him – he was a celebrity and a flawed human – it’s not my place to grieve Robin Williams. But the day I found out he took his own life, two years after my dad did, was one that shook me up. It put the first little crack in my silly brittle shell.

I didn’t know him, but he was a real firefly for a lot of people. There’s no non-cheesy way to say this, so just remember that you’re a firefly for someone today, and that you have fireflies all around you.

Firefly-ness. Whatever that quality is that sends a glimmer of joy—or hope or courage or strength—someone else’s way. How’s that for a definition of sainthood? Does that mean we can add Robin Williams to the list?

It’s so easy to develop a general, angsty disappointment in people. I remember, as the sheltered child of evangelical missionaries, being assured: “Sinful humans will let you down every single time. No one is trustworthy, so you need to cultivate your relationship with God above all else. Forget friends, and definitely don’t waste your time on boys. Nobody else is worth it.”

It turns out that’s true, if what you expect from people is the level of piety our early saints are privileged to enjoy—a reputation smoothed to a glowing burnish by reverence and time, with nothing but a few vague stories of miracles and courageous deaths remaining. The warty, everyday humans you meet in your congregations and communities certainly can’t live up to the perfection of that distance and near-mythology.

—

“Piety, piety, but where is the love that moves mountains?”

Maria Skobtsova wrote these words in one of the many frustrated, scathing diary entries aimed at her fellow religious leaders, who she felt allowed their focus on the strict keeping of fasts and liturgical calendars to draw their eyes from the love of God and neighbor. Maria was constantly at odds with the hierarchs of the organized church in her day, yet she is now canonized as an Orthodox saint: St. Maria of Paris.

Maria was once an atheist, a poet, and the elected mayor of a small Russian town during the Bolshevik Revolution. After moving to Paris and undergoing a spiritual awakening, she became a monastic—but, somehow, she convinced her higher-ups to allow her to do it her way. Rather than joining a cloistered community as was the norm, she rented a house that she transformed into a refugee shelter for individuals battling homelessness or addiction. While most Orthodox nuns at the time foreswore “the world” and turned their eyes inward, Maria dove into the streets with a gusto, often staying up late into the night laughing and smoking with those she served. When the Nazis invaded Paris, she and her priest forged baptismal certificates for as many of their Jewish neighbors as they could, and when 13,000 Jews were held in an indoor stadium until they could be transferred to a concentration camp, she helped smuggle children out in trash cans. She was killed in Ravensbrück concentration camp after two years of suffering there. Her last days and hours were described as anything but faith-filled, heaven-focused, or remotely martyr-like—and can you blame her if, in the end, she despaired?

Maria was a firefly, fueled by love. She was far from perfect. She was a saint. Learning about her has taught me so much, stretched my heart, and turned me towards God. That’s the point of saints, whether they bake cookies for children or bludgeon the literal devil with a literal sledgehammer.

My father spent the months before his suicide in darkness, like Maria, and his memory has certainly not remained perfectly shiny. He was a person, with flaws. I still listen to his sermons from time to time, and I still remember him with love. I’d still consider him a firefly. What’s more, the more I look for the fireflies around me—from my Uber driver to my childhood best friend—the more I find them.

Who are the fireflies surrounding you? Who are your living saints—the imperfect, shining people whose presence or example helps you muddle through?