This is an excerpt from the article “American Lutherans and their Hymnals,” by Mark Granquist which will appear in the Spring 2024 Issue of Word & World.

A key theological distinctive of the Lutheran Reformation was Martin Luther’s understanding of the Word of God, and how encountering that Word created faith in the believer. In worship that Word became real when it was proclaimed to the people through preaching and sacraments (both equally Word), which is why the worshippers had to actively hear, understand, and participate in worship as the Word came to them. Along with preaching and sacraments, however, there was another way in worship in which Christians heard and participated in the Word, and that was through the singing of hymns. Luther knew that joining in congregational hymn singing was a key way Christians both heard the Word and expressed their faith. The combination of text and music in a hymn was distinctively effective in deepening faith, and over the centuries hymn singing became an integral part of Lutheran identity. Lutherans are a singing people.

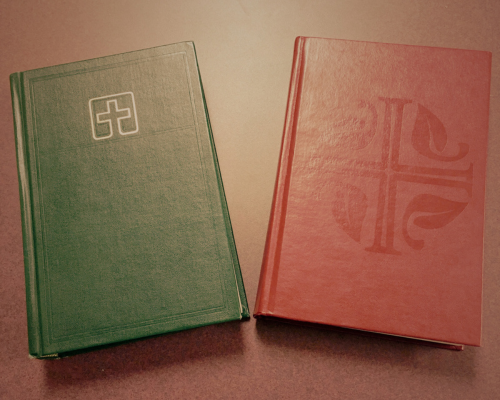

Lutherans developed a rich tradition of hymns and hymn singing. Over the centuries, as Lutherans expanded through Europe, North America, and eventually all around the world, their hymn traditions were broadened by contacts with hymns and music from other Christian traditions. Beginning with Luther’s first collection of hymns in 1525, Lutherans have developed countless hymnals to pull together their songs of faith. But each hymnal is a theological act; although there are innumerable hymns, not all hymns (even some of our favorite ones) are equally helpful in the task of creating faith. And as language and religious tastes change over time, some older hymns drop out of favor, while others are added. So, the making of hymnals is a complicated and often controversial task, and there is often much conflict involved; given the centrality of hymns to Lutherans and their faith, they become possessive of their hymns and their hymnals. Change is difficult.

From the sixteenth century on, Lutherans in Europe developed regional hymnals based on their areas and linguistic traditions. These variations were further complicated by inter-Lutheran theological debates, such as those between the Lutheran scholastics and the reforming Pietists, between theological traditionalists and rationalists, and between modernists and conservatives, just to name a few. Over the centuries changes in musical and lyrical expression also complicated things, to the point that there were often more competing hymnals, some official and others not sanctioned, that vied for attention. Every time there was the need for a new hymnal, there were competing visions of what should be included (and excluded) from the previous versions. As Lutheran hymn scholar Gracia Grindal has observed, “each hymnal is something of an attack on the previous hymnal.” The reason Lutherans fight so much over hymnals is that hymn singing is so central to their faith lives. All hymns are not created equal.

When Lutherans began to immigrate to North America, they brought with them these hymnal traditions and controversies. In the ubiquitous immigrant trunk, many immigrant Lutherans brought with them several religious books; usually the Bible, Luther’s Small Catechism and collections of his sermons, devotional works such as Johan Arndt’s True Christianity, and the Psalmbook (hymnal) of their variety of Lutheranism. These were for them more than just religious books, these were their portable churches, especially important because there were often no Lutheran congregations in the places they were headed. As they developed their congregations and denominations, these hymnals were the key to maintaining their faith in a foreign land. Think of the comfort that an old and deeply felt hymn could have had to a stranger in a strange land.

Times have changed drastically in the centuries since Lutherans first immigrated to America. Across the board, people in contemporary America have fewer opportunities to sing together than they did in the past, and this is a trend also found in Christian congregations. Hymn-singing is a theological art that does not simply happen by accident; it has to be built and nurtured. The question is whether Lutherans and other Christians can continue the traditions of hymn singing for which they have become known. This is not simply a question of musical taste or preference. If, as was suggested at the beginning of this essay, it is a matter of how people encounter the Word of God being proclaimed to them in worship, then the continuation of these hymn traditions is of the essence of the evangelical (gospel) tradition itself. Time will see how this crucial form of hearing the Word of God is maintained for and among future generations.