The story of the Tower of Babel just seems to keep on keeping on. In order to slow humanity’s quest to touch the heavens—a quest which reveals how we think nothing should be beyond our reach, capacity, or possession, and which has its roots in reaching for forbidden fruit—the Lord God, “confused the language of all the earth” (Genesis 11:9). And we in the church, be it a Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant church, seem all too happy to keep that confusion going. Insider lingo, ancient terminology, and unfamiliar language can, as often as not, confuse and separate people from the shared life of faith, which is our goal. The way that we talk and the words that we use, as important as they may be, can at times work against understanding and connection.

Years ago, a group of Lutheran seminary (that’s a four-dollar word for “school,” by the way, a school that is for pastors and other religious professionals) students were studying for an exam in their worship class, working on terms and definitions. As they studied, one of their professors (of church history, not worship) passed them by, and, hearing them break down terms like “narthex,” and “paten,” and “thurifer,” asked what they were studying for. “The vocab section of our worship final,” they replied. As the story goes, their professor shook his head and said, “If I find out that any of you got an A on this exam, I’ll personally see to it that you’re drummed out of seminary!”

Why? What was his point? Our use of insider language can, at times, get in the way of what really matters. Insider vocabulary can, if we are not careful, obscure the very gospel that we are trying to communicate. We should, therefore, have our priorities straight and our emphases in the right places. And our language is the place we need to start being thoughtful—inclusive, if you will.

A basic question we ought to ask is, how important is it to use any given word when we are talking about God, or Jesus, or human beings, or worship?

For example, do we absolutely need to use the word “paten” to identify the little, shallow plate (also sometimes called a diskos, not to be confused with a discos which is either a species of fish native to the Amazonian River basin, or a sporting event in track and field) that the bread of the … oh my, shall we call it “The Eucharist” (which is a Greek word that means thanksgiving that emphasizes what the priest is doing), or “The Lord’s Supper” (which is more of a description of who is in charge), or “Communion” (which is also derived from a Greek word, koinonia, which means something like “participate in fellowship,” or simply “connect”)? Words are hard.

Anyway, where was I? Right, the paten. Do we need to use that word to describe the little plate that holds the bread which, with the wine, makes up the sacrament? (And here we go again. A sacrament is “a Christian ceremony that is believed to have been ordained by Christ and that is held to be a means of divine grace or to be a sign or symbol of a spiritual reality,” that’s according to Merriam W., and for Christians there are, depending on your tradition, seven or two or, in some cases, none really.) Does knowing that that little plate is called a paten make any difference to the promise of the words, “This is my body, given for you,” or “This is my blood, shed for you and for all people for the forgiveness of sins”? No, it doesn’t. So, if you didn’t know what a paten was before, go ahead and forget it, it doesn’t really matter.

But there is, naturally, some vocabulary that is necessary. This is true, I imagine, for every branch of the Christian tree. Certainly, Lutheran Christianity does have its own set of terms—Lutheran-isms, if you will—that simply can’t be discarded or replaced.

Here, then, is a humble offering of three critical words that a visitor or someone getting to know the Lutheran tradition needs to know in order to navigate the Lutheran world and the Lutheran understanding of the Good News.

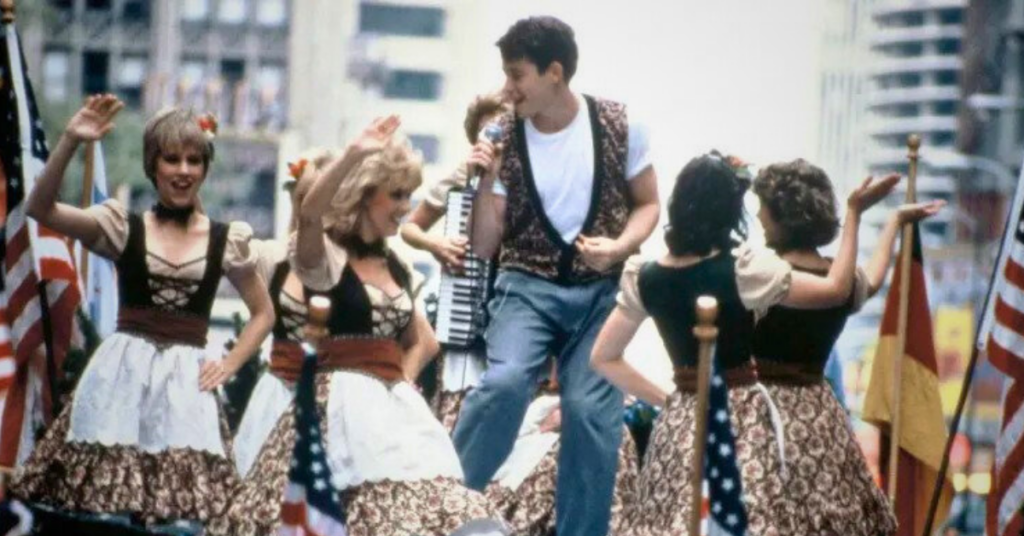

The great Ferris Bueller famously said that “-isms in my opinion are not good. A person should not believe in an -ism, he should believe in himself.” Taking Bueller’s lead, let’s start there, with the word that Bueller’s quotation embodies: sin.

Sin

For Lutherans, “sin,” is anything that separates us from God and/or from our fellow human beings. Sin identifies both specific failings, and one significant part of our basic human-ness, that is to say, the way we humans kind of always are. Sin has to do with both conduct and character. When it comes to our conduct, sin is both about things we have done (often called sins of commission) and things we have failed to do (often called sins of omission). Think about those biblical passages that talk about what we are supposed to do and to not do—to love the Lord our God with all our heart and to love our neighbor as much as we love ourselves (check out the Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy 5, or Jesus’ teaching on the two most important commandments in Luke 10:25-28, and good luck living up to the parable that follows). When it comes to character, sin has to do with human brokenness and the reality that despite our best efforts, and sometimes precisely because of our best efforts, human beings tend to be more selfish than selfless, and prone to trust our own instincts and efforts over what we hear from God and Jesus. There are sins, and there are the sinners who sin them, which, for Lutherans, is everybody no matter how good or holy they may appear. As Paul says in Romans 3:23, “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.”

Understanding this, how do we think about the answer, the solution to the problem of sin and sinners? This brings us to our next key term: sola.

Sola

Sola is a Latin word that means “alone” or “solely,” and, truth in advertising, by using this term I am fixing to cheat. Instead of just one -ism I’m going to walk through three, which, if you think about it, is kind of ironic when the word means “alone,” but I can’t help myself. After all, Lutheran-isms often express the paradoxes of the Christian faith. So, there are three “solas” that from the earliest days of the Lutheran Reformation were important. In Latin they are: sola scriptura, sola gratia, and sola fide; in English: Scripture alone, grace alone, faith alone.

Sola scriptura/Scripture alone

When it comes to living the Christian life, and understanding our Christian identity, Scripture—the Bible—is the foundation. Nothing, for Lutherans, is more important or a higher authority than the Bible. Scripture introduces us to God, shows us who we are and what it means for us, and, above all, brings us Jesus Christ, who is God’s Word incarnate. (Alright, I did it again, cheating, sneaking another term in there. “Incarnate” here kind of means “God with flesh on.” Think “chili con carne,” chili with meat, and that’s Jesus, God’s Word and love literally embodied for us.) For Lutherans nothing can take the place of the Bible in terms of knowing who God is and what God intends for us, not church mission statements, not human traditions, not our instincts, not nature, “Not,” as the Cowardly Lion put it, “nobody, not no how!”

Sola gratia/grace alone

The core message of the Bible, whether we are reading from the Old or the New Testament, is that God’s intentions for us, at every turn, come from a place of graciousness. Over and over again God is described as gracious (see Exodus 34:6, Psalm 145:8, Joel 2:13; Jonah 4:2). The answer to sin, for Lutherans, is not working harder and harder to be better and better (although we can and probably should try). The only answer to sin is forgiveness, which is ours because of God’s grace. Grace means God is at work, not us. Grace means that God will make things right, not that we will, or can, or must. When Lutherans talk about grace we are pointing not to what we deserve from God, as though we are somehow special, rather we are pointing away from ourselves to God and God’s goodness, which alone is the answer to our need for healing and wholeness. As Paul used the word in Romans 3:24, God’s grace is a gift which brings us “the redemption that is in Christ Jesus,” and Ephesians 2:8-10 echoes this, “by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God—not the result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are what he has made us….” It is grace alone that brings forgiveness and redemption, and this is pure gift.

Sola fide/faith alone

And how can this gift be ours? by faith alone. Only faith, trusting both truths—that we are sinners, and that God loves and forgives sinners out of God’s own goodness and graciousness—can bring this home to us. Faith, trust that these are promises are for us, is what brings God’s grace to life in our lives. Receiving God’s grace has nothing to do with our deserving it, or earning it, or even participating in it. Receiving God’s grace is possible only through faith, believing that when Jesus says that God did not send him into the world to condemn, but to save, that this includes us; believing that when the pastor says, “This cup is the new covenant” in Christ’s blood, “shed for … the forgiveness of sin” it is spoken, right now, to you, about you, for you; believing that, as Ephesians says, “by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God (Ephesians 2:8). Faith alone can make sense and reality of these promises, when we come to know that these promises are ours.

These three things, alone (sic), are a sort of summation of the Lutheran understanding of the Good News. And they bring us, in a roundabout manner, to one last word which captures the whole shebang: justification.

Justification

Probably the single most important word for Lutherans, and for understanding Lutheran theology and practice, is justification is about how we sinners are made right with God. Martin Luther famously said that “if this article [justification] stands, the church stands; if this article collapses, the church collapses.” What he meant is that justification is the final absolute, it is the one point at which we cannot give any ground, it is non-negotiable. Justification is about being made right with God, and we need to be clear on just how that happens. The fourth article of the Augsburg Confession, one of the foundational documents that outlines the Lutheran understanding of the Christian life, theology, and Scripture, says this about justification:

“…it is taught that we cannot obtain forgiveness of sin and righteousness before God through our merit, work, or satisfactions, but that we receive forgiveness of sin and become righteous before God out of grace for Christ’s sake through faith when we believe that Christ has suffered for us and that for his sake our sin is forgiven and righteousness and eternal life are given to us. For God will regard and reckon this faith as righteousness in his sight, as St. Paul says in Romans 3[:21-26] and 4[:5].”

Justification is about God’s grace, ours through faith, which is made known to us first and foremost through the Scriptures. And if we get nothing else exactly right, this one we need to nail down, because this is the basis of the Christian faith, and therefore the Christian’s life. It’s like this,

“…if you get this right, you’re gonna be okay, no matter what else you screw up. (And trust us, you will screw up [*see above on “sin”]) So let’s say it again: Ephesians 2:8-9 says that we are saved by grace through faith. Furthermore, this faith is not our own doing. This faith is the gift of God, not the result of works, so that no one may boast about they were able to work up enough faith to get on God’s good side” (Crazy Talk: A Not-So-Stuffy Dictionary of Theological Terms, 131).

This is just a start. There are, of course, other terms or concepts that we would want to define and understand in order to go deeper in learning to speak “Lutheranese,” from the simple, like forgiveness, or sanctification, or vocation, or assurance, or law-and-gospel, to the more complex, such as simul iustus et peccator, antinomianism, the two kingdoms, and kenosis. But here is a start.

With these simple Lutheran-isms you can’t go wrong. Start with these three (or is it five, or seven, or ten?) and sooner than later you’ll be speaking a fluent Lutheranese.

Want to know more about the insights and gifts available to us through the Lutheran tradition? Check out our Faith+Lead Academy course, Lutheranism: Bound and Free, with instructor and Luther Seminary Professor of Reformation History and Theology, Mark Tranvik.

You’re right on in that jargon or the unique language of any institution makes in exclusive rather than inclusive. Modern church music is a testament to that. Without becoming too esoteric, as you have done with some of the terms you’ve used, there is a language common to Lutheran churchgoers that doesn’t include the more arcane terms to which you’ve referred, and that language tends to isolate those who don’t speak it.

We now attend a UCC church in Sahuarita, Arizona. These are folks who not only espouse the teachings of Jesus, but they also act on them. They have also simplified the service by consciously eliminating jargon.

A breath of fresh air for me is the absence of liturgy. First, long term Lutherans have it memorized, leaving visitors and casual attendees fumbling. Secondly, and most important, is that after having spent most of my working life as a high school counselor, I firmly believe that almost all people are good. Yes, they screw up occasionally, and perhaps “saved by Grace” gives them some comfort. But I see it as unnecessary and punishing to recite “that I have sinned against thee by what I have done and by what I have left undone.” And there you have a bit of jargon using the Elizabethan “thee” rather than “you,” as if God can’t comprehend modern American English.

I enjoyed reading your piece. It would be fun to discuss it at more length if we ever have the opportunity.

Lawrence Severt