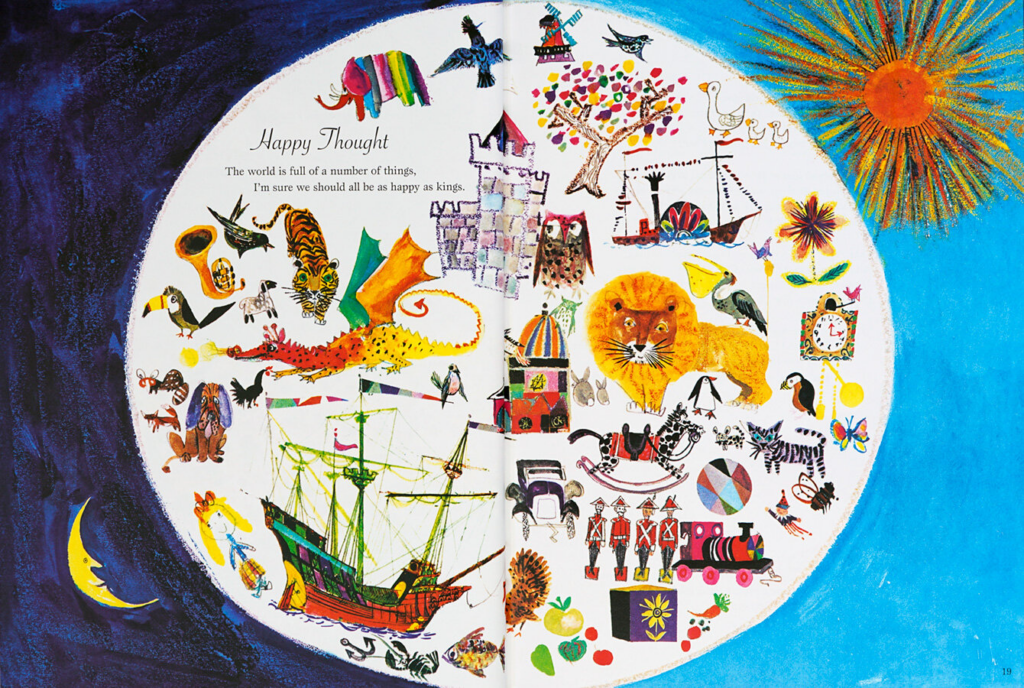

The world is so full of a number of things,

I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings.

—Robert Louis Stevenson, “XXIV. Happy Thought,” A Child’s Garden of Verses

I didn’t learn this two-line poem as a child or from my parents or kindergarten teacher. I learned it in college from my aged theology professor, Michael McDaniel. He and his wife Marjorie were family friends and frequently opened their home to me, a bewildered Yankee in North Carolina.

Though college itself should have been what opened the world to me, it was the McDaniels’ home that captivated my imagination—or, to be more specific, their books. So many books! Miles of books! And here I thought I came from a bookish family. We had nothing on the McDaniels! Michael loved to relate how, whenever an astounded visitor would ask, “Have you read all of these books?” he would always reply, truthfully if misleadingly, “Some of them twice!”

It was not just the quantity of books, though, but their range. My dad is a theologian too, but he read only theology. (Now he also reads about bees, bears, and sustainable agriculture. But that’s it.) My mom added carefully selected novels, a cornucopia of cookbooks, volumes on psychology and mythology. But her more expansive interests were hampered by the relative lack of access: this was the pre-internet era, with the nearest Waldenbooks a half-hour’s drive away and a full two hours to a proper indie bookstore.

The McDaniels’ library was a lifetime’s work of collection and curation (and evidently some runaway spending). Here I discovered that Madeleine L’Engle had written books for grown-ups alongside my fresh discovery of P. G. Wodehouse; on the McDaniels’ sofa I giggled myself into a fit over Psmith in the City. I found oversized photo books of art and architecture, and volumes about kinds of music I didn’t even know existed. Histories of the Renaissance sat alongside the print companion to the silly British TV show Root into Europe.

Michael’s favorite theologian (besides Luther, of course, because of course Luther, Michael admired and emulated the reformer’s irascibility) was Hugh of St. Victor, a medieval monk of the eponymous abbey in Paris. In class we read Hugh’s Didascalicon, an attempt to organize all the world’s knowledge—not in a creepy surveilling Googlesque kind of way, but in an attentive creature’s appreciation of the breadth of the Creator’s handiwork kind of way. Michael would occasionally try his hand at his own organization of all creaturely knowledge, taking as much obvious delight in the effort as any child exploring a wonderful garden.

And he would often quote the little poem from Stevenson, which maybe he had learned as a child himself, and maybe formed him and the theologian he would go on to be: as happy as a king, because the world was so full of things to explore.

Michael’s delight in everything stayed with me because it modeled a way of being a theologian that suited my own wide-ranging interests. Theology is the “study of God,” but the study of God always points back in the direction of “the study of the number of things that God has made.” Nothing is a priori off limits.

[Brian Wildsmith. Illustration from A Child’s Garden of Verses. 2008.]

That isn’t to say theology and theologians have mastered all aspects of creation—certainly not! (Ask me sometime what I think about theologians waxing eloquent on economics with no awareness of their staggering ignorance of the topic. Go on, I dare you.) But everything in God’s world can in principle become a matter of delighted exploration.

But as I think back on it now, there was another reason Michael made such an impact on me. He never told us to be curious. He never invited, encouraged, or harangued us to be curious. He just was infinitely curious himself, and so inadvertently became a model of curiosity. Not because he was trying to, but simply because he was that way.

This strikes me powerfully now because, it seems to me, there is a growing sense that a person’s curiosity can’t be trusted. It’s too narrow, or biased, or misguided, or useless in achieving some other valuable end. We are told nowadays what exactly it is that we’re supposed to “get curious” about. Don’t trust your instincts, don’t follow where your own interests lead you. Instead, pay attention to your betters and wisers who will inform you as to the right thing to get curious about.

And after all, why not listen to people who know better than you? We do ourselves a good measure of harm insisting on our own way and refusing the accumulated wisdom of our mentors and elders and ages past. Presumably the experts know better what is worth “getting curious” about. So along with exhortations to “get curious,” I note the growing number of people obediently accepting the charge and directing their attention accordingly.

The problem is that what drives this is not the object of curiosity itself, but the desire to please a superior. Or possibly one’s peers. Surely we can all remember with dismay the gradual recession of our childhood passions as the early adolescent urge to conformity swallowed our souls. How we started watching and listening to the same things as our friends and proved our uniqueness by becoming utterly indistinguishable from one another! Nothing is more shameful at that age than curiosity outside the ever-shrinking Overton window of social approval.

I’m sure that serves some important developmental function, but I’m also sure it’s something to grow out of. A right and proper gift of adulthood is the moral courage to return to the transcendental curiosity of childhood, back to the wonder at the number of things, claiming the right to follow where curiosity leads without being reprimanded: “No no, not that, get curious about this.” A petty and moralistic spirit scolds curiosity. A generous spirit endows it with a kingly dignity.

Are there areas curiosity ought not go? Of course. I think we can all agree that gain-of-function research on viruses is a super duper bad idea. Luther warned against speculating on double predestination and God’s will apart from his revelation in Christ. We can acknowledge that all increases in knowledge also lead to increases in danger, because the better you understand something the better you can manipulate it, from radioactivity to the human genome.

But such pursuits give themselves away in that they have departed from delight. They are no longer about the wonder of encounter with the new and the other but have been redirected to control and use.

Which is again why exhorting someone to “get curious” is so utterly wrongheaded. It’s trying to control and use the gift of curiosity for some other purpose at odds with curiosity itself.

[Brian Wildsmith. Illustration from A Child’s Garden of Verses. 2008.]

Curiosity is not something you can program or engineer—not in someone else, but not in yourself, either. You can’t make yourself curious about anything. It happens or it doesn’t (as any good friend who has patiently listened to an unending recital of the minutiae of a hobby can attest).

And actually, in this way, curiosity bears striking parallels to faith. Luther protested the received scholastic account of faith as something that the will generates by its own decision. No, Luther countered, faith lies at the level of the will itself, and one of the most robust human experiences is the will willing what it wills regardless of what one wants to will! (See Romans 7 if you’re not sure what he’s talking about.) The will can’t will itself into faith. So… now what?

Now… the Holy Spirit! Something outside yourself comes upon you, steals over you, overtakes and transfigures you. It’s from the outside in, not from the inside out. The Holy Spirit captivates you by the gospel and so faith is brought into being out of nothing. You don’t create or generate faith: it is rather the response evoked by something outside of you.

There is a strong structural analogy here to curiosity—a First Article parallel to this Third Article work. The natural disposition of newborn humans is openness, a receptivity to what comes from without, starting with mother’s voice and breast, and growing over time to other faces and textures and smells to furry animals and cuddly toys to the backyard and books and rain puddles and Christmas trees and cookies.

But even here, as any observer of children knows, for all the common passions (cookies are universal) each child has unique interests and delights. My son’s earliest passion was frogs. We neither fostered nor repressed the frog-centeredness. Froggies captivated him, and that was that.

It is such a joy to watch curiosity unfold in children: to watch just what it is that comes along and raptures them, to follow the unfolding of that openness in any number of unpredictable and controllable directions. When Jesus said, “Let the little children come to me and do not hinder them, for to such belongs the kingdom of heaven,” I think he is paying honor to this very openness, which in the domain of creation is curiosity and in the domain of justification is faith.

How can faith possibly justify? How can curiosity possibly be trusted?

Both come down to whether God really does live and reign in and among us. If not, then faith is laughably inadequate and curiosity a vain distraction from someone else’s ideology.

But if Christ is Lord, and we are his—then, after all, we should be as happy as kings! And exult in the number of things he has put in his world for our enjoyment.

In memory of Michael McDaniel (†18 December 2003) and Marjorie McDaniel (†29 March 2023).