Look on my right hand and see,

For there is no one who acknowledges me;

Refuge has failed me;

No one cares for my soul.

-Psalm 142:4

“Help! I need somebody.” -John Lennon

A gift of God has been rediscovered in the world of Protestantism. It’s been bubbling up in the soil of desperate and exhausted pastors and church-goers alike. Cracks and fissures started showing themselves when church leaders’ lives started falling apart. The people they shepherd, left wounded, looking for someone else to care for them; while the pastor bled out on stage.

You know the stories. Or maybe, you were the story.

One of my old pastors once stood on stage, looking defeated, and told us, “I’ve given you all my best stuff.” And walked out.

In Morris Dirks’ book Forming the Leader’s Soul: An Invitation to Spiritual Direction, his testimony from his life as a pastor goes something like this:

- I remember stepping off the stage on a Sunday morning only to be informed that a drunk driver had killed Cal, my dear friend and fellow elder. His daughter died the next day.

- I remember the deep pain I felt when a long term leader and friend left the church over the position we reached regarding the role of women in ministry.

- I remember looking at a key church leader as we sat in my driveway after a difficult meeting. I said, “I need your help and I need you now.” Nothing changed.

- I remember dedicating a baby at the hospital, knowing that we were preparing for impending death, not celebrating life.

- I remember conducting the funeral of a young man who loved God, but, in a moment of despair, blew his head off with a shotgun.

- I remember sitting with a married couple as the husband informed his wife that he was in an affair that subsequently ruined their marriage. There was no guilt or shame as he described his total loss of integrity.

- I remember sitting with a friend and pastor on our team a few days before Christmas as the police chaplain informed him that his son had overdosed on heroin.

- I remember struggling with what the doctor finally categorized as “chronic fatigue” while I continued to face the weekly demands of ministry, concluding each weekend by preaching four times.

Wave after wave. In the life of church leaders, there is no time to fully process all the emotions, let alone go through stages of grief, before the next one lands in their lap. Grief and burnout have become their companion and often there is simply no place to lay their weary head. What was born out of a relationship with the Trinity morphed into some sort of survival plan where spiritual neglect, relational isolation and identity issues grew like fungi in the dark. What kind of church environment could foster such sickness?

If there’s been one thing that’s glaringly clear in my own relationship with the Protestant-American church, it’s that her spiritual mindset has often been very individualistic. Growing up in the Evangelical/Baptist tradition, a lot of emphasis was put on our personal saving faith. So much so, that we skipped right over present day life and into “well, at least we’re going to Heaven when we die.”

In college, I had a brief stint of “soul winning.” There we were, walking down the sunny and manicured neighborhood streets of Santa Clara, CA. Usually in groups of four. Us girls wearing some form of khaki skirts or jean skirts and the guys wearing ties. We were young. Eighteen, nineteen, twenty, fulfilling our Saturday morning three hour duty of soul winning. Evangelizing, or really, proselytizing.

I don’t know about you, but usually when I’ve been on the receiving end of such an act, I pretend like I’m not home. Who actually wants to discuss whether they’d go to Heaven or not when they die, with someone they’ve never met? Some people do, I suppose. But not me. And that was always the question: “Hi, we’re from such and such college, home of such and such church and we were just wondering if you were to die today, if you knew if you’d go to Heaven?”

Simple question. Yes or no. Right? The truth is, we had no idea what we were doing. The few times we were actually invited in, we were presented with the complexities of people’s stories that didn’t fit within our checklist of whether or not one could go to Heaven. I’m ashamed to admit, the only reason we were there was to check off our own boxes. Win souls to be a good Christian. Be a good Christian to get into Heaven. We weren’t there to be anybody’s friend.

There was this innate belief within us and within the religious system we were in. It burdened our shoulders and clouded our minds. It narrowed our vision and cupped our ears. The belief that I had the power to change people. There wasn’t much talk of that ever illusive Third Person of the Trinity. But there sure was some good ‘ol fashioned American Individualism and her co-dependent parent, Pride.

How did our faith in God tie us to each other? We had no idea.

The culture of church ministry generally is not kind to fostering vulnerability from its leaders. Again, Morris Dirks writes:

“Leaders often experience a sense of brokenness in dramatic ways, yet the culture of ministry makes it very difficult to reveal this neediness to others. Some of the confirming statements made to me include: ‘My failures are not safe to share. My attempts at being the so-called authentic, transparent leader are always met by elders with looks of concern.’ Another wrote, ‘The challenge to be transparent and honest is one that I’ve struggled with. Will people allow me to be honest?’”

When Dirks hit the wall, he was so overcome with shame that all he could do was isolate.

Who will return this call for help? Perhaps we’ve hurt ourselves by viewing these calls for help with disgust, blame, and judgment—using God to stamp approval on our lack of compassion.

What is a way that brings life and consolation? What can draw us out of ourselves towards God? Rather than towards the desolation we find inside ourselves, alongside judgment and shame?

Soul Friends

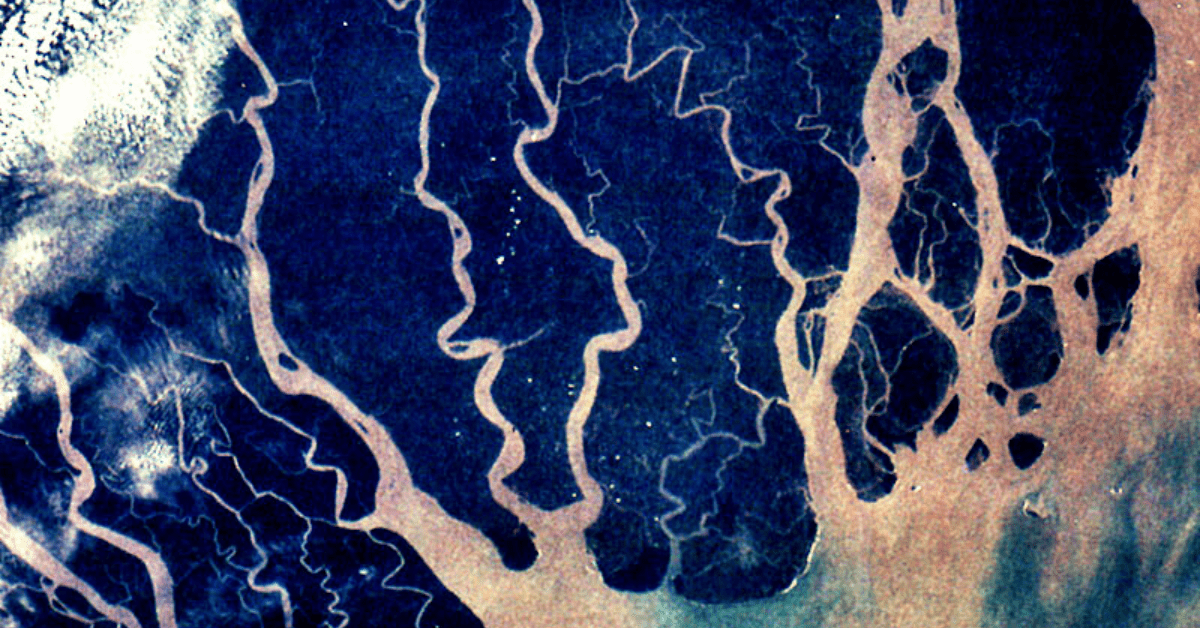

(image credit: A Blossoming Friendship, Phyllis Gorsen.)

The discipline of Spiritual Direction comes from within our church history. It’s not a new fad, it was relied upon heavily by our church mothers and fathers. The voices of Tertullian, Cyprian, Ambrose and Jerome; Augustine, John Cassian, Saint Symeon, Aelred of Rievaulx, Catherine of Sienna, Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross, Francis de Sales, Jane de Chantel and Francois Fenelon, all ranging from as early as 100 AD up until the seventeenth century; the Holy Spirit speaks through them and says, “We bring good news!” “How great an advantage it is for us to be able to consult someone who knows us, so that we may learn to know ourselves,” as Teresa of Avila said.

Or, as John O’Donohue writes in his beautiful book Anam Cara: A Book of Celtic Wisdom, dating back to the 6th century, a person that helped you in matters of the soul, bringing you back to yourself and God, was called an anam cara. A “friend of the soul … a person to whom you could reveal the hidden intimacies of your life. This friendship was an act of recognition and belonging. When you had an anam cara, your friendship cut across all conventions and categories. You were joined in an ancient and eternal way with the friend of your soul.”

Henri Nouwen wrote that Spiritual Direction is a “relationship initiated by a spiritual seeker who finds a mature person of faith willing to pray and respond with wisdom and understanding to his or her questions about how to live spiritually in a world of ambiguity and distraction.”

Spiritual Direction differs slightly from what we often call “spiritual mentors,” or discipleship, because it is more specific. It focuses on the common denominator between two Christians: the Holy Spirit. A spiritual director lives a life of contemplative action, knowing that the two should not be separated from one another. They demonstrate wisdom in matters of the spiritual life and are respected among other spiritual leaders. They listen with empathy and have learned how to listen to God on your behalf. They know how to ask good questions, exploring new pathways for you to notice where God is present in your life. They are immersed in Scripture, fleshed out with a relational theology; bringing out the ways God’s Word speaks in everyday life. They are dedicated to “speaking the truth in love” (Ephesians 4:15)—a difficult lesson to learn for any Christian, but especially for the spiritual director.

As Wilfrid Stinissen writes in The Gift of Spiritual Direction: On Spiritual Guidance and Care for the Soul, “To harmonize tenderness and strength in relation to the confidant is one of the guide’s most difficult tasks.” In addition, they are able to live with your unresolved difficulties. There is no pressing need to fix you. They are able to live in the tension of an “unfinished life.” Knowing that Paul’s words ring true when he wrote, “It is God who is at work in you to act in order to fulfill his good purpose” (Philippians 2:13). And last but certainly not least, there is safety in confidentiality, compatibility and trust. As Thomas Green clarifies in his book, The Friend of the Bridegroom: Spiritual Direction and the Encounter with Christ, “Spiritual direction, like the sacrament of reconciliation, requires strict confidentiality. The person being directed shares his inner self, his most personal possession. It belongs exclusively to him.”

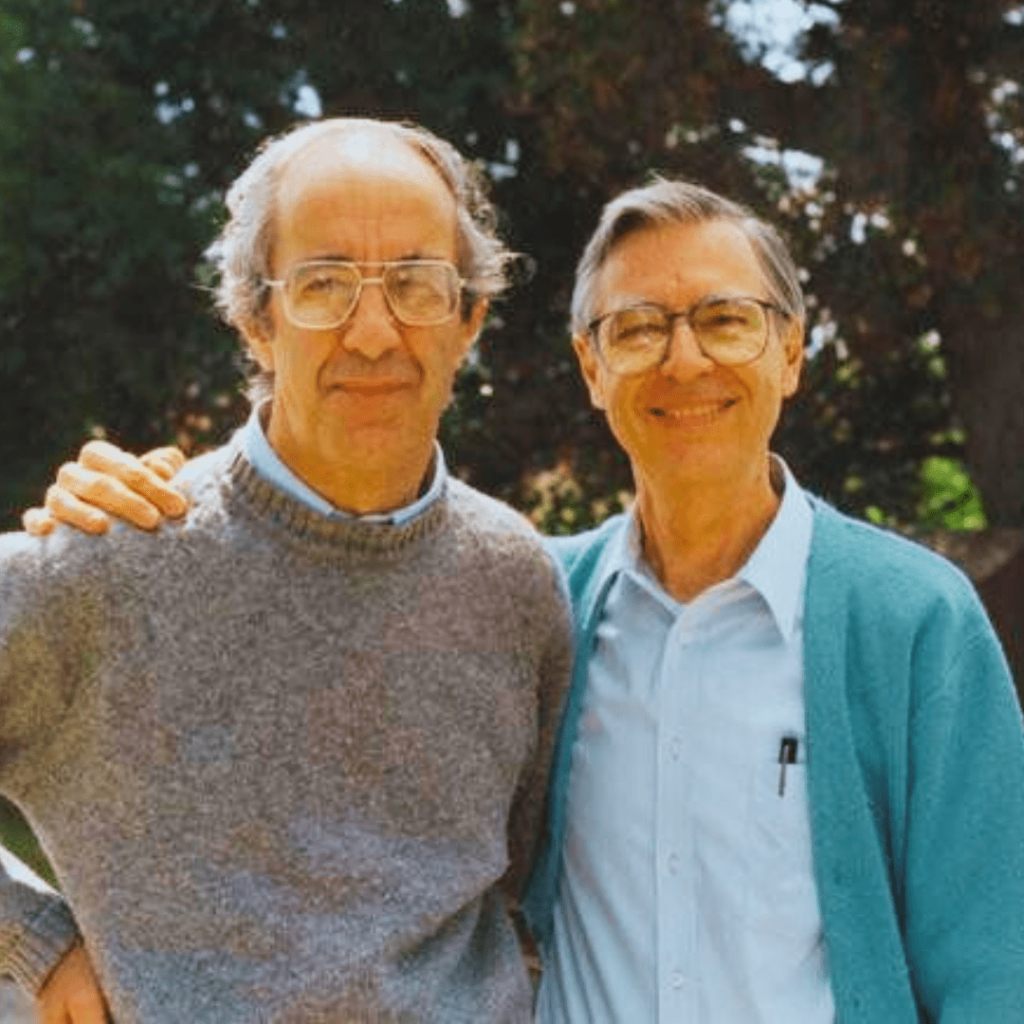

[Henri Nouwen and Fred Rogers]

Some of us have had soul friends without even knowing it. I’ve had the gift of two. The first one has been in my life for twenty years now. Our relationship can pretty much be summed up in Henri Nouwen’s definition. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was getting someone to whom I could bare my soul. She would listen and listen some more. She was one of the first people who ever asked me, where do you sense Christ’s presence in your life? Through her friendship, I learned how to pay attention to my life and discovered that God was indeed there with me. She was and is a friend of the soul.

Laura M. Fabrycky, in her Comment magazine essay, The Freedom of Friendship, illuminates: “In the lonely crowd, among the pluralities of our networks, contacts, and associates, a friend is the one who is still willing to know us, singularly and freely. In that respect, said C.S. Lewis, ‘every real Friendship is a sort of secession, even a rebellion … a pocket of potential resistance.’’

Angela has been my pocket of resistance. And in the language of the Kingdom of God, that is a treasure.

A return to this rich spiritual discipline is bringing fresh waters into the stale spiritual life of many church ministries and their leaders; thrown out in the seventeenth century for fear of “sacerdotalism.” A fancy word that Gerald May addresses in his book Care of Mind/Care of Spirit. He writes that for many Protestants, “there have often been special theological problems with the idea of one person advising another on intimate matters of the spirit. Much of the concern here has to do with sacerdotalism, the possibility that the methods of personality of the spiritual director would supplant the role of Jesus as the prime mediator between God and the individual human being.”

Perhaps we’ve gone too far. We’ve relied too much on the role of the individual. Is it not part of the role of the church to not just teach us about the Gospel but show us? We look to Jesus to show us the way, and He looked to His Father, and we, His Bride, have the Holy Spirit knitting us together. It longs for us to pay attention and discern its voice. We are beloved. We need authentic spiritual companionship. My aunt converted from Evangelicalism to Catholicism looking for that rich and historical depth. Similarly, friends have converted to Greek Orthodoxy. I have watched in awe as they’ve navigated life with grace, conviction, and contemplation.

I remember standing in my kitchen around 12 years ago with my friend. We were lamenting yet another breakdown in my church body at the time. And that’s when it hit me. My friend asked, “what do you want, Janell?” I didn’t even think. Out of desperation I responded, “I’m tired of everything having their neat little boxes and categories. I’m tired of all the compartmentalization. I want all the dividers to be removed and God and life and church and friends can somehow mix together. I’m tired of labeling everything either Christian or non-Christian. I want to be whole.”

She looked at me and said, “yeah, me too.”

That’s the journey I’ve been on since. During the Pandemic, someone I follow on Instagram (because let’s be honest, I was on there A LOT during the Pandemic), wrote about graduating from a Spiritual Direction program here in Portland, OR called Soul Formation. I was curious and checked out their website. They were speaking my language! I felt butterflies in my stomach and urgency in my bones. Could this be a way forward in my journey with Jesus and for others? By January of 2023 I found myself beginning to learn the language of spiritual direction.

It can be a way forward in the life of the church. The voices of church history have heard our cries of help and have answered. We have asked, where is the good way? An ancient way has emerged out of our rubble. A soul friend has reached out her hand and has said—

I can help. I can help you walk in it.