“One-take Wendy,” they called her. Stand her by a painting, point a camera at her, and she would create brilliant real-time, unrehearsed content in—you guessed it—one take. Wendy was so good, that by the 90’s and early 2000’s, she was flown around the world to tour the museums and galleries filled with paintings she had only seen in books and postcards. And we watched, by the millions, as she taught nations an art history course. Wendy was a natural onscreen. It suited her, but her talents weren’t cultivated for television. She didn’t even own a television. As a matter of fact, she had never owned a television. Wendy was a hermit: the consecrated kind.

She started her religious career at the age of 16. The teaching order she belonged to, the Sisters of Notre Dame, paid for her to be educated at Oxford. She was advised not to make friends, but that didn’t stop J.R.R. Tolkien from being impressed with her work translating medieval Latin. So impressed, he encouraged her to stay on and get her Ph.D., and teach. While she went on to teach in South Africa for many years, she didn’t feel called to academia. She had a physical and emotional breakdown that caused her to be released from her vows, the Pope allowing her to be consecrated as a hermit. She stayed with Carmelite nuns, living in a tiny RV trailer, eating one meal a day, and spending the rest of the time in prayer, reflection, and writing to pay for her upkeep; translating Latin, and writing articles on art history. A chance encounter with someone from the BBC while Wendy was on a rare hermit’s outing, and the rest is history. Seriously, just YouTube her. You’ll get it.

In a reflection in her book, Spiritual Letters, Wendy wrote of her vocation:

“I wanted to become a nun, because that was the only way I could see to belong totally to God. I understand now, of course, that every way of life can be given to Him, and that a nun is no more potentially holy than a bus driver or a dentist. But subjectively, in personal terms, to become a nun was necessary for me. I have come to the conclusion, looking back, that a bus driver or dental Sister Wendy would have fallen pathetically by the roadside.”

Her public facing career, or “apostolate,” as she referred to it, took time away from being with God, which she saw as her true career. In an interview on Fresh Air, host Terry Gross probes the apparent contradiction.

“What about the disparity between your cloistered spiritual life and the 30,000 miles of travel to 12 countries that were required of you to shoot the PBS series? […] Do you—have you seen this as a sacrifice? Or have you welcomed the opportunity to actually be in the world? See the world?”

Sister Wendy’s answer was honest.

“Oh, no, no. It’s a sacrifice. I would be delighted if I could, say, hand over the task to somebody else. No, I would never have wanted to do this and I sometimes look at the Lord with a rather quizzical air. You know, I was so lucky. I had all that wonderful solitude and silence. And then, he asks me to give up parts of it. Well, if you—if I really want to love and serve him, then I must try and do this with as big a smile as I can manage, but it would never have been my choice. […] But I think that’s a sacrifice that I’m called upon to make because any gift any of us have is never just for us. It’s for sharing.”

————————

The reason I like to write about Sister Wendy for predominantly Protestant audiences is because she often sounds rather Protestant. I suspect it’s less a lean into Protestantism, and more our ears picking up on the language common to Christ’s followers. She wasn’t afraid to tell you the bad news, because she had the Best News. In another example from her Spiritual Letters, we see this unflinching passion spill out as she’s encouraging a friend.

“That loveless slum you see in yourself is quite truly you—I won’t pretend otherwise, but it is you seen in the light of God. The “you” that He passionately loves, that He chooses to be most intimately possessed in a love-union—that you is the poor thing you experience as your true self. So, despair is the last thing to feel, rather a blazing surge of hope and gratitude that His love doesn’t depend at all on our beauty and goodness. But there is even more joy to it than this, because we just can’t see our poverty unless he shows it …

So to see it is clear proof that He is present, lovingly and tenderly revealing Himself to you. It’s the contrast you are experiencing—can you understand? How do you know you are weak and unloving? Only because the strength and love of Jesus so press upon you that, like the sun shining from behind, you see the shadow.”

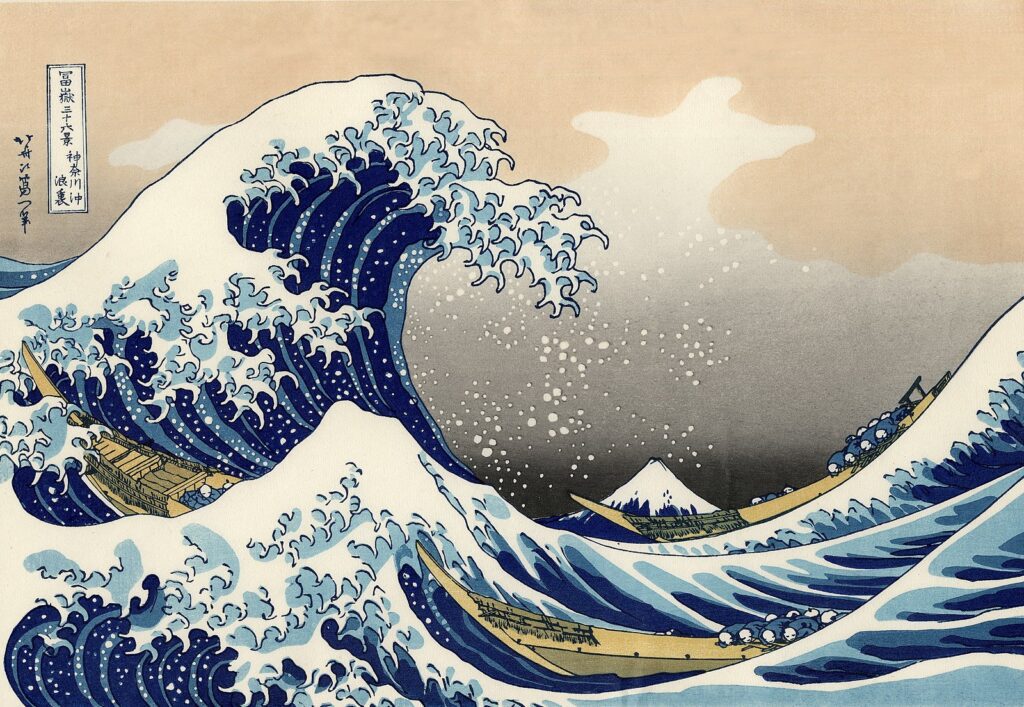

That line, “You see the shadow.” That’s quite the picture of our need. It certainly sharpens the contrast between our version and, well … reality. Wendy’s low anthropology often spilled out in her art critiques. In The Art of Lent, Wendy reflects on Hokusai’s iconic painting, The Great Wave, by preaching Romans at us.

“We cannot control our life. As Hokusai shows so memorably, the great wave is in waiting for any boat. It is unpredictable, as uncontrollable now as it was at the dawn of time. Will the slender boats survive or will they be overwhelmed? The risk is a human constant; it has to be accepted—and laid aside. What we can do, we do. Beyond that, we endure, our endurance framed by a sense of what matters and what does not. The worst is not that we may be overwhelmed by disaster, but to fail to live by principle. Yet we are fallible, and so the real worst is to forget our fallibility, to refuse to recognize failure and humbly begin again. Ash Wednesday reminds us of our constant need to acknowledge and confess our fallen humanity, to repent of the past and throw ourselves on the loving mercy of God. For we have been assured that nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord (Romans 8.38–39).”

Episcopal priest, Robert Farrar Capon, echoes this paradox in his book, The Foolishness of Preaching. He sets a scene: A girl is drowning while a horrified group watches helplessly from the beach. The lifeguard swims out to save the girl, and yet both drown. This is not the storyline we were expecting. The camera zooms in on a clipboard left lying on the seat in the lifeguard tower. It says, “It’s all okay, trust me, she’s safe in my death.”

Sounds like Lent to me!

Wendy was gifted by God to be a hermit. She believed it, and I do, too. God also, in God’s way, took an extraordinarily committed introvert on a globe-trotting adventure and into the homes of millions of people talking about Jesus. Yeah, that sounds like God. Wendy was uniquely fitted for her work, none of which was planned. I mean, how could one plan being an Oxford educated amateur art historian, popular television presenter/religious hermit? Thankfully for us, God did! I’m not putting Wendy up as an exception, though I do think she was exceptional, but as an example of what God can do in and through our work. If you are a fisherman, God can make you an apostle. If you are a hermit, God can place you in the homes of millions, simultaneously! The cognitive dissonance of it is sheer fun, but the impossible is God’s business. After all, God made a saint out of a sinner like me!

I love this so much. Thanks for writing, Josh!