What do you do when it seems your whole world has fallen apart? Everything you once thought to be true now seems to be a built on faulty logic, lies, or by people with control-issues. All of the core beliefs that you built your life upon now seem to be crumbling underneath you.

This can be a terrifying experience for many people.

I’d like to use this post to provide a visual guide for understanding this process and offering possible ways to navigate it.

Take a Breath

Before we begin, I invite you to take a deep breath.

It’s OK.

This is actually a normal part of life and how we grow in maturity as humans.

My Personal Experience of Deconstruction

My first experience of feeling the cracks in the foundation of my worldview happened in college. I grew up in a loving home, as a pastor’s kid, in the Evangelical imagination of the 70s and 80s. It was a wonderful world, truly. Everything made sense. I knew what was right and what was wrong. I knew who was in and who was out. And, I knew that it was my job to lovingly help all those people who were on the outside to find their way to the inside, where they can share in all the love of God that I experienced. Sounds nice, right? It was for me.

Two things happened to me right after high school. The first was that I went to work with an art company and was surrounded by people from radically different worldviews…and they weren’t “bad” people. I actually liked them a lot and their various perspectives made sense.

Second, I went to Wheaton College in the late 1980s. It was supposed to be the safe choice to get a solid liberal arts education within the confines of “good theology.” Then I met Dr. Lake for my first course in Systematic Theology. I was so excited, because I have always been a bible/theology nerd.

Dr. Lake assigned a book on Liberal Protestant Theology…and didn’t tell us it was wrong! Almost every word in that book challenged my core beliefs about the Bible, God, salvation, etc. The core of my inherited worldview was so dependent upon one unified theory that even reading one little book and seeing one little crack in the foundation of my faith sent me spinning.

I never lost my faith in God, or my trust in Jesus. However, the shaking I experienced in that class produced two outcomes in me. First, it led me to drop my double major in Biblical Studies and Art and focus all my energy in pursuing an art career. “God doesn’t need another pastor,” I told myself, “God needs an artist that is ‘sold out’ for Jesus.” Second, it sparked a curiosity in me that led me across multiple theological landscapes and ultimately to a Ph.D. in Missional Leadership from Luther Seminary (completed in 2015).

My faith was deconstructed.

Then it was reconstructed.

Then deconstructed again, and reconstructed.

This process has been happening throughout my life…praise God!

Theology Beer Camp 2023 and Deconstruction

In October, I attended a conference called Theology Beer Camp and the theme was Christianity (or Faith) after Deconstruction. I really appreciate what one of the speakers said. Dr. Rubén Rosario Rodrígez reminded us that deconstruction is not a singular event. It is the normal process of doing good theology. It is critical thinking.

I would add that the deconstruction-reconstruction process is a core element of spiritual formation and contemplative action. We must continually reflect critically on what we are doing, why we are doing it, and what we think God is inviting us to do next. That process takes time and intentionality. This is why I teach spiritual formation. I want to help people embrace God’s deconstruction and reconstruction in their lives. It is how we grow.

A Technical Definition

The term deconstruction is a buzz word in some circles. It is a breath of fresh air and liberation for some. It is a source of fear and trepidation for others. Technically, it is a term that is most often associated with the philosopher Jacques Derrida and is related to the philosophical understanding of the relationship between text and meaning.

The Oxford Dictionary defines it as

a method of critical analysis of philosophical and literary language which emphasizes the internal workings of language and conceptual systems, the relational quality of meaning, and the assumptions implicit in forms of expression.

While the group of super-nerds at Theology Beer Camp is fully aware of the technical meaning, the way we used the term was much broader and is, in reality, a shared human experience.

It basically addresses my opening question, “how can I believe in God, or any stable, ultimate reality, after something has rocked/shattered/challenged my worldview?”

The Visual Guide

The inspiration for this post came from an experience I had at TBC last week. My favorite presentation happened on Saturday morning when Dr. Reggie Williams and Dr. Aaron Simmons presented on Ethics after Deconstruction. Dr. Williams reflected on the construct of “whiteness” as the definition of human in western culture and how that toxic foundation must be deconstructed. Dr. Simmons drew from his extensive work with Kierkegaard and existentialist philosophy. Williams and Simmons were then interviewed by Tim Whitaker, the host of the podcast The New Evangelicals.

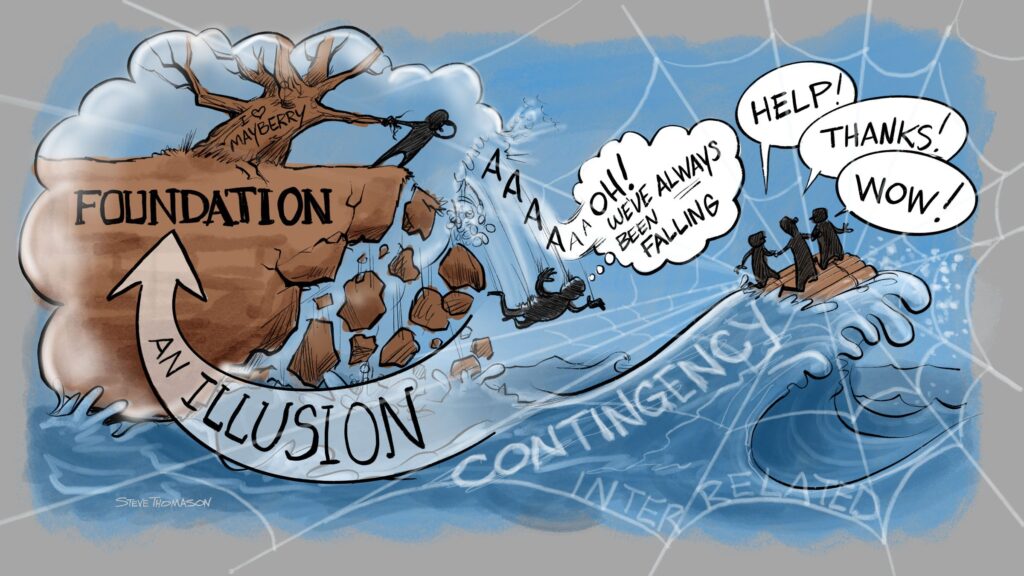

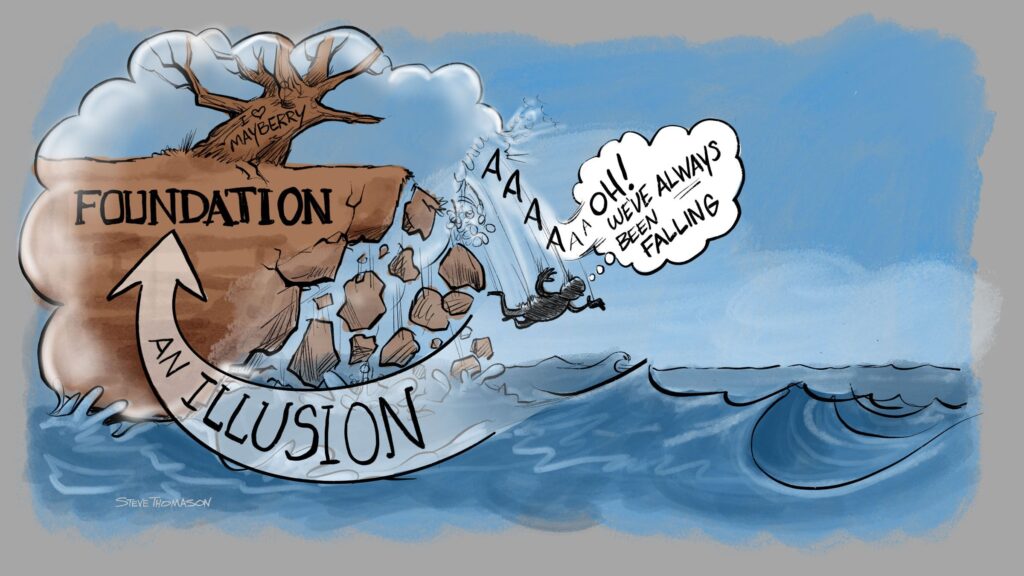

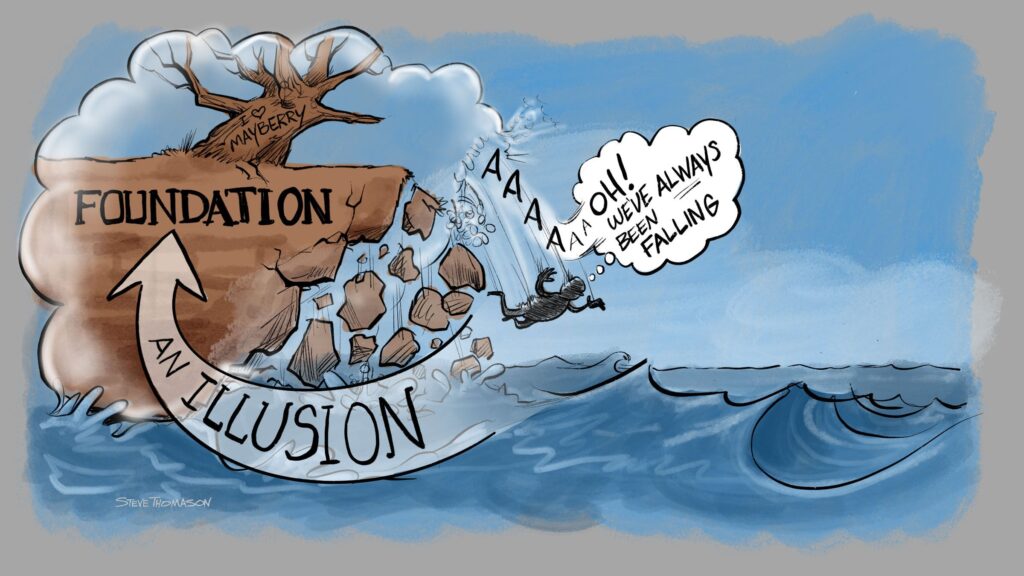

I went back to my room after the presentation and the following image emerged in my imagination. I took out my iPad and this is what happened.

Now let’s break the image down into its parts to explore the process of deconstruction and reconstruction.

Simmons named three false foundations that have constructed much of our modern theological imagination:

Objectivism – the metaphysical myth that there is a distinct divide between the observer and the object being observed. This is the core of modern scientific methodology that has led to the dissection and destruction of nature and other humans.

Certainty – the epistemological myth that we can build our conceptual frameworks on certain undeniable and indisputable truths.

Absolutism – The ethical myth that there are certain values that are either good or evil in all circumstances, regardless of context.

Whitaker connected this to the rise of White Christian Nationalism and Williams responded by calling it the propaganda of Mayberry (the fictional home town of the Andy Griffith Show). When the false foundation of Whiteness is being challenged, it is understandable why people will take any measures necessary to hold on to it (including overt racism, propaganda, and storming the capital).

Simmons stood on the edge of the stage and looked down. “Kierkegaard,” he told us, “said that life is like standing on the edge of the abyss and looking down. We hold on to our past as long as we can. But when we fall, we realize that we have always been falling and the sure foundation we thought we were clinging to has always been an illusion.”

This is a terrifying moment.

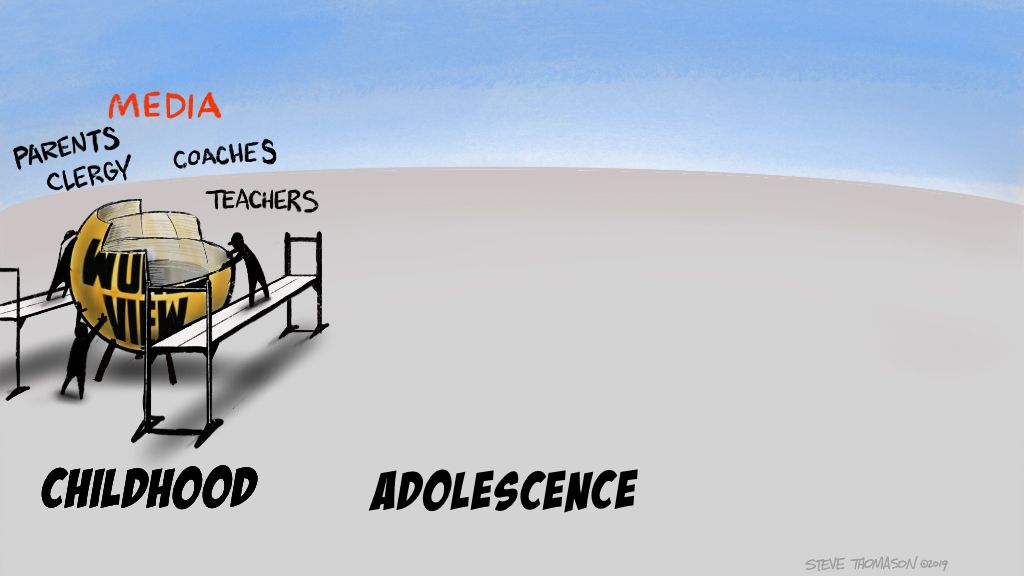

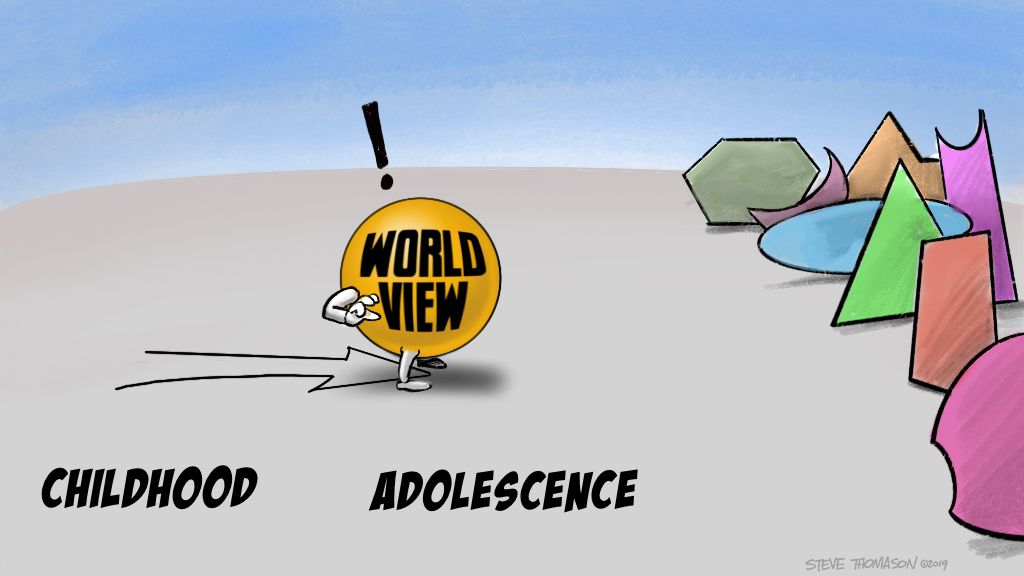

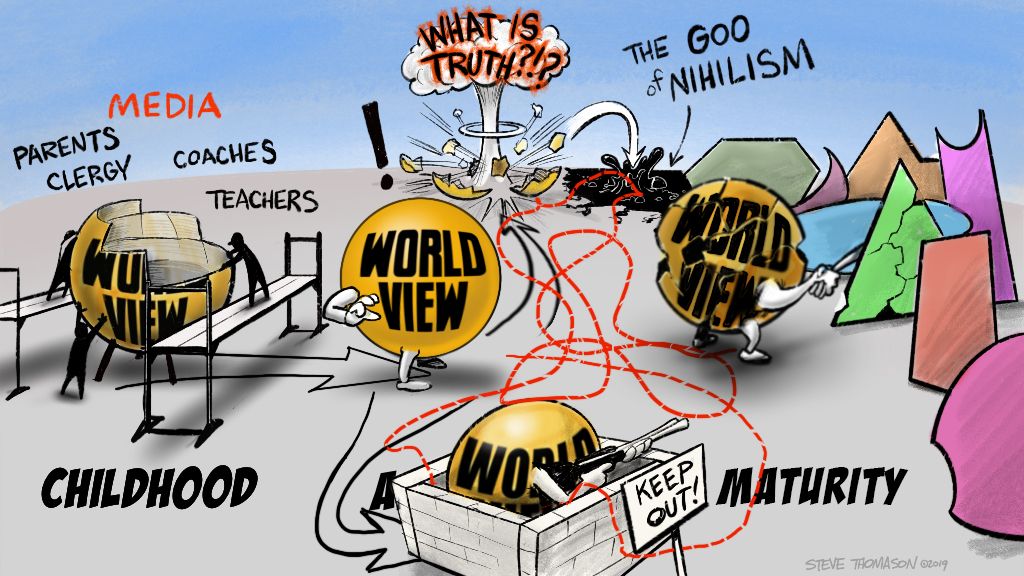

I want to switch to a different set of visuals that I created several years ago. This visual presentation was designed to help the ninth graders in the Confirmation program that I led at Easter Lutheran Church to be prepared for the deconstruction that would inevitably happen in their lives (and was probably already occurring).

I told them that our worldview—our foundation—is constructed for us by the people who raised us. This is an important part of human development. Everyone has a worldview constructed for them and we don’t get to choose where we are born.

Those of us who live in “Modern Western Society” are constantly surrounded by people who are very different from us and have grown up with radically different world views. Our first encounter with this difference can be shocking and be the catalyst for the deconstruction process (like my college experience).

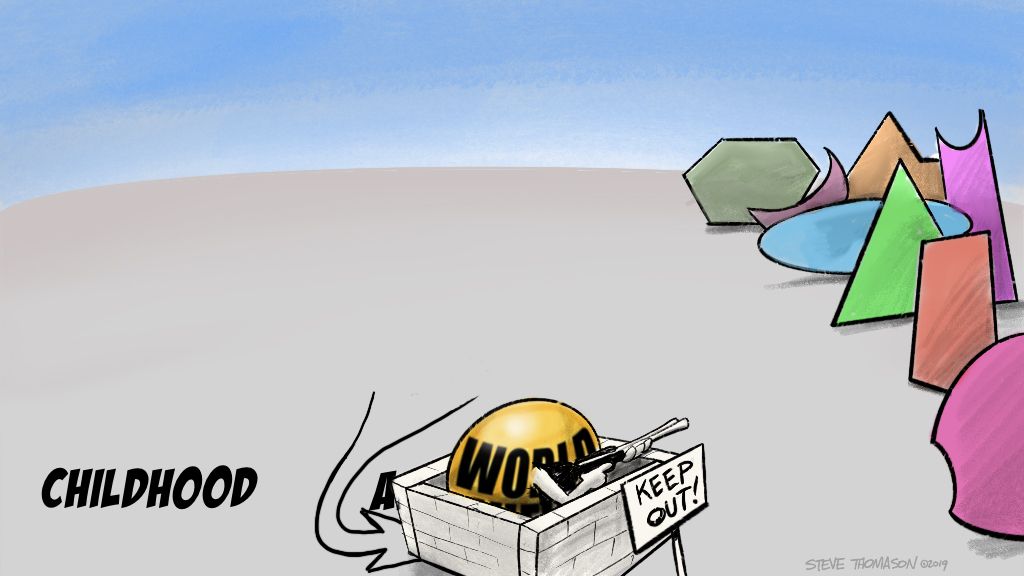

There are two natural human responses to this:

The first is what I call entrenchment. When we see something different than us, the sympathetic nervous system kicks in the fight, flight, freeze or fawn response. We build up strong protective walls around our world view that clearly marks the difference between “us” and “them.”

There are two forms of entrenchment:

The first comes from the flight or freeze response. We hide inside our encampment and pretend like there is no one else out there. “Live and let live,” we tell ourselves, “and don’t bother me.” We rationalize this as “living in peace.”

The second comes from the fight response. We look at the “other” as an enemy and a threat. Therefore, we must either convert them to become like us, or they must be eliminated for the sake of our own survival.

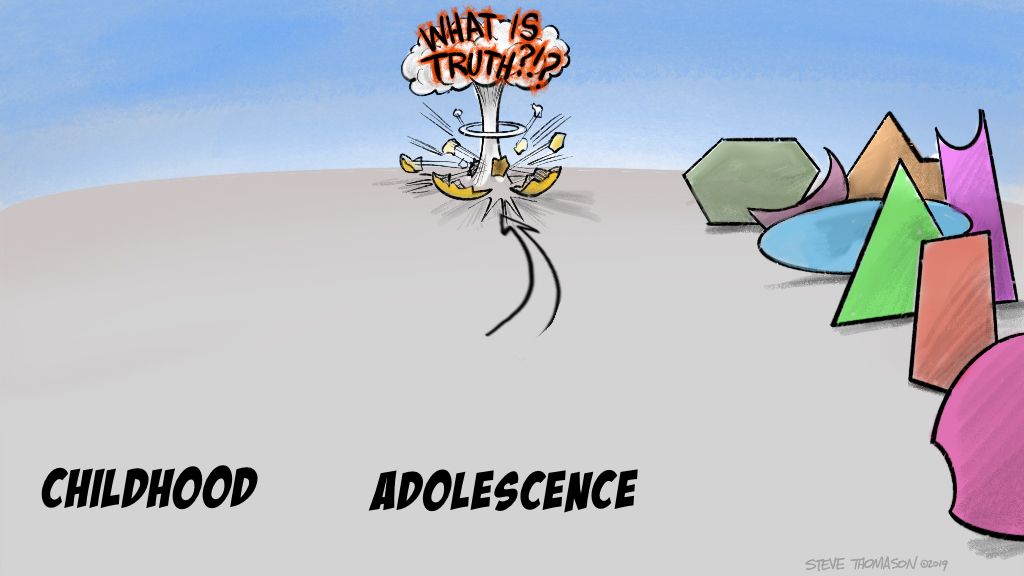

The second natural human response is at the other extreme of entrenchment. It, too, is connected to the fight, flight, freeze, or fawn defense mechanism, but it flees the situation by saying, “oh, if my worldview/foundation is not the only way to understand reality, then it must be utterly wrong.” We then proceed to deconstruct it completely and never try to reconstruct anything. We operate with the notion that there is no such thing as truth and we are all on our own.

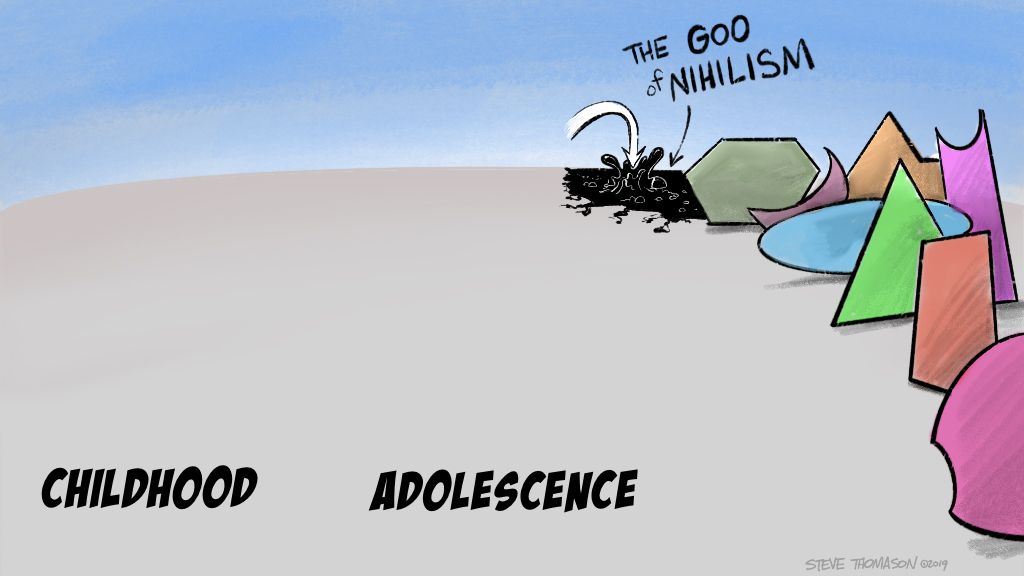

I call this the “goo of nihilism.” Many young people buy into the myth that it is possible to live life without, or above, a worldview. This is what Robert Kegan would call the fourth order consciousness where an individual is aware of the limitations of their inherited worldview, but believes it is possible to live in pure objectivity and looks down upon all cultural frameworks as primitive or old-fashioned.

This connects us back to the first illustration. We realize that we’re all falling together.

So what do we do?

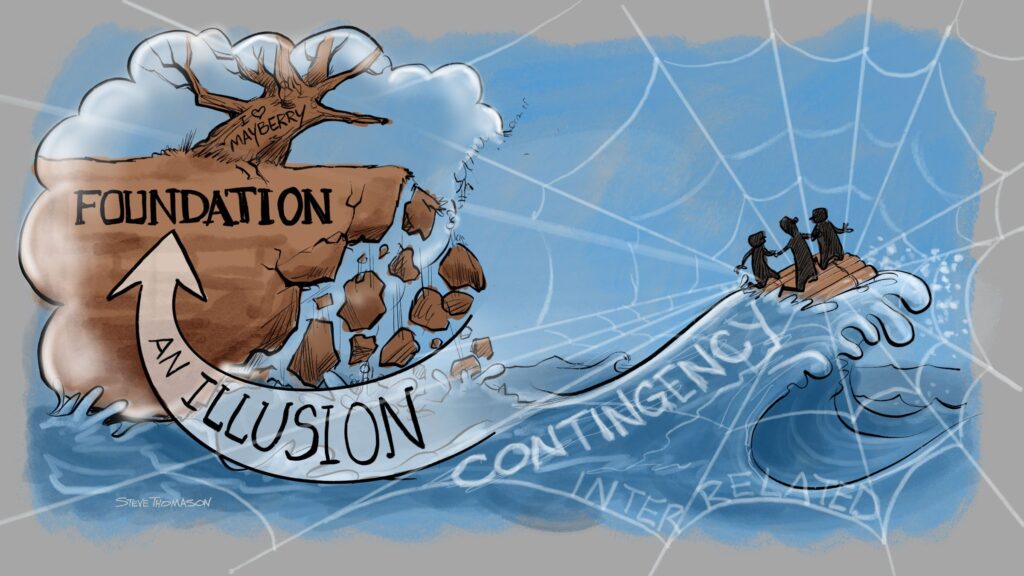

Simmons offered three alternative frameworks that will help us navigate the waters of a pluralistic reality. First, he named that reality is contingent. There is uncertainty in the very fabric of the universe. This is what Quantum mechanics has helped us understand. The universe is less like a machine or a fixed building that is grounded in a firm foundation, and more like an ever-unfolding web of interrelated connectedness.

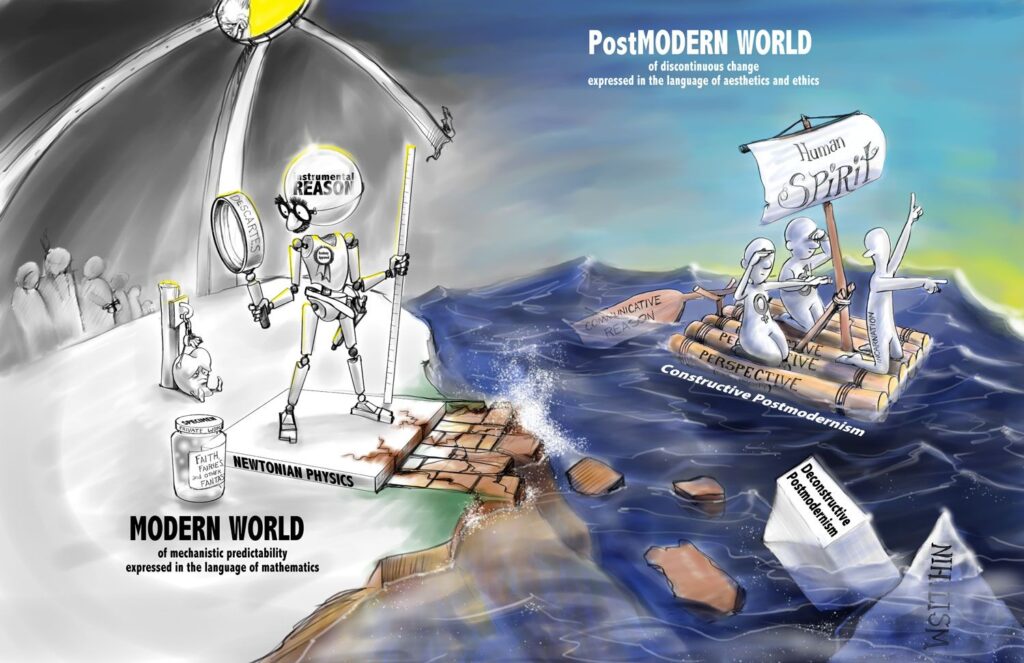

Here I must bring in yet another illustration that I created in 2012 when I was doing my PhD and trying to wrap my mind around the shift from modernity to “post-modernity” or from foundationalism to postfoundationalim (see this page for my work on a postfoundational frame and open and relational theology).

Notice in this illustration that I distinguish between a “deconstructive postmodernism” and a “constructive postmodernism.” In this metaphor the “goo of nihilism” is an iceberg in the sea of uncertainty. If we deconstruct and never attempt to make sense out of reality and work together with others who differ from us, then what kind of world will we have?

Constructive postmodernism, on the other hand, is the attempt to function within a communicative rationality. This is the realization that if humans bring their differences into conversation with each other, we can form a new kind of platform on which to navigate the uncertainty of an open future. This is not a foundation, but more of a raft that is constructed by various worldviews lashing themselves together and being steered by open communication.

I want to highlight how this illustration folds my theology into the mix. Here we see my anthropology (what is human?), pneumatology (who is the Holy Spirit?), and Christology (who is Jesus?).

Anthropology. Humans have agency in the universe. We have the ability to use reason and intuition to choose our conversation partners, figure out how to tie our diverse perspectives together, co-create a functional rationality, and try to steer the direction of our shared life. We also have spirituality. By this I mean that we have the quality of spirit and are more than the sum of our biology.

Pneumatology. Notice what function the human spirit serves in this illustration. It is a sail. The power that ultimately drives the ebb and flow of the uncertainty and chaotic beauty of the ocean/universe is not the human spirit, but the wind and the moon’s gravity. This is one aspect of how I see the work of the Holy Spirit. Human spirituality is the process of positioning ourselves in relationship to the wind in such a way that we can go somewhere.

Christology. Jesus is the third figure on the raft. Jesus is the incarnation of God; God in human form. Some have seen this character as third gender. Some see it as gender/human unification. In either case, it represents the theology that Jesus came as a particular human in a particular time to show us the way to be fully human in relationship with the divine.

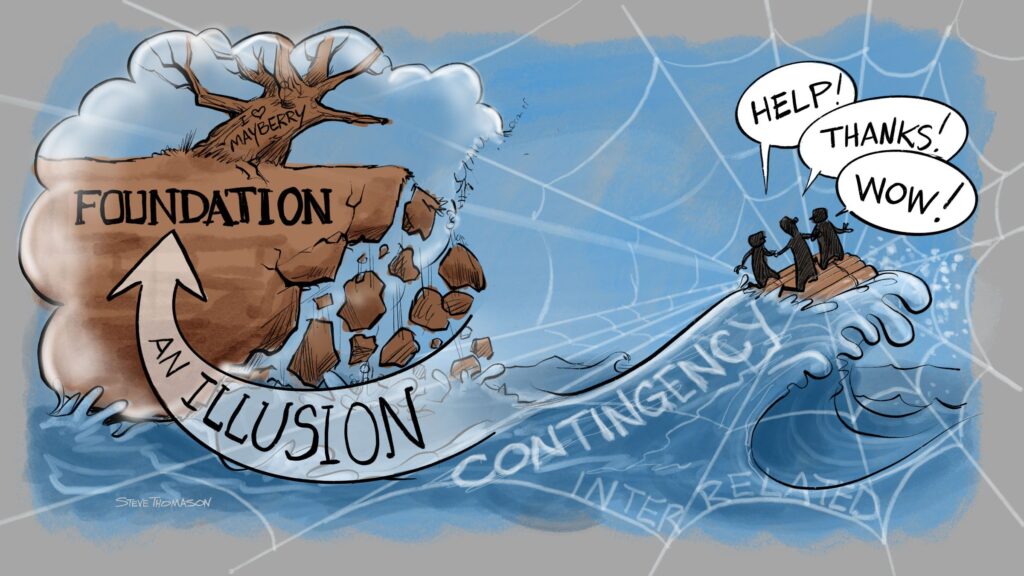

Simmons frames the post-deconstruction reality with three contrasting perspectives to the false foundations mentioned above. He invites us to operate in an attitude of

humility,

hospitality, and

gratitude.

Simmons connects these attitudes to Ann Lamott’s three essential words of prayer:

Help,

Thanks, and

Wow!

I left my ninth graders with this summary image. The realistic picture of life is that we will vacillate between the extremes of entrenchment and explosive nihilism throughout our lives.

Connecting this to Spiritual Formation

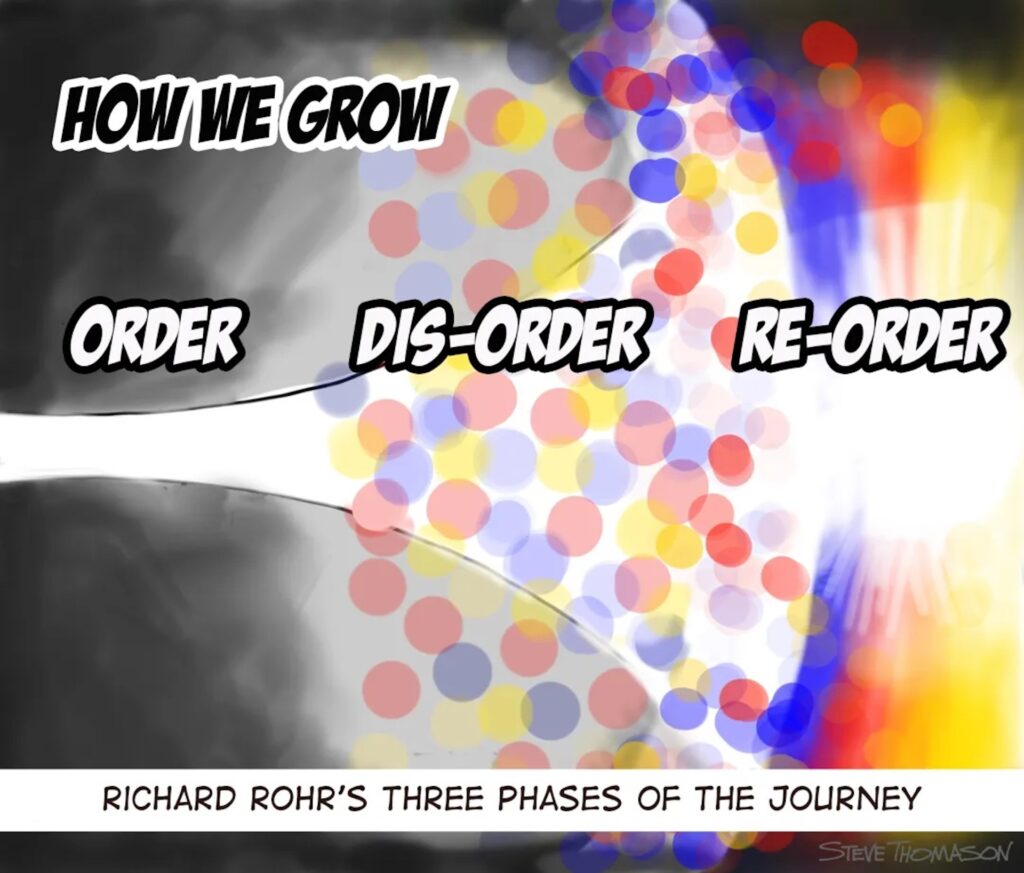

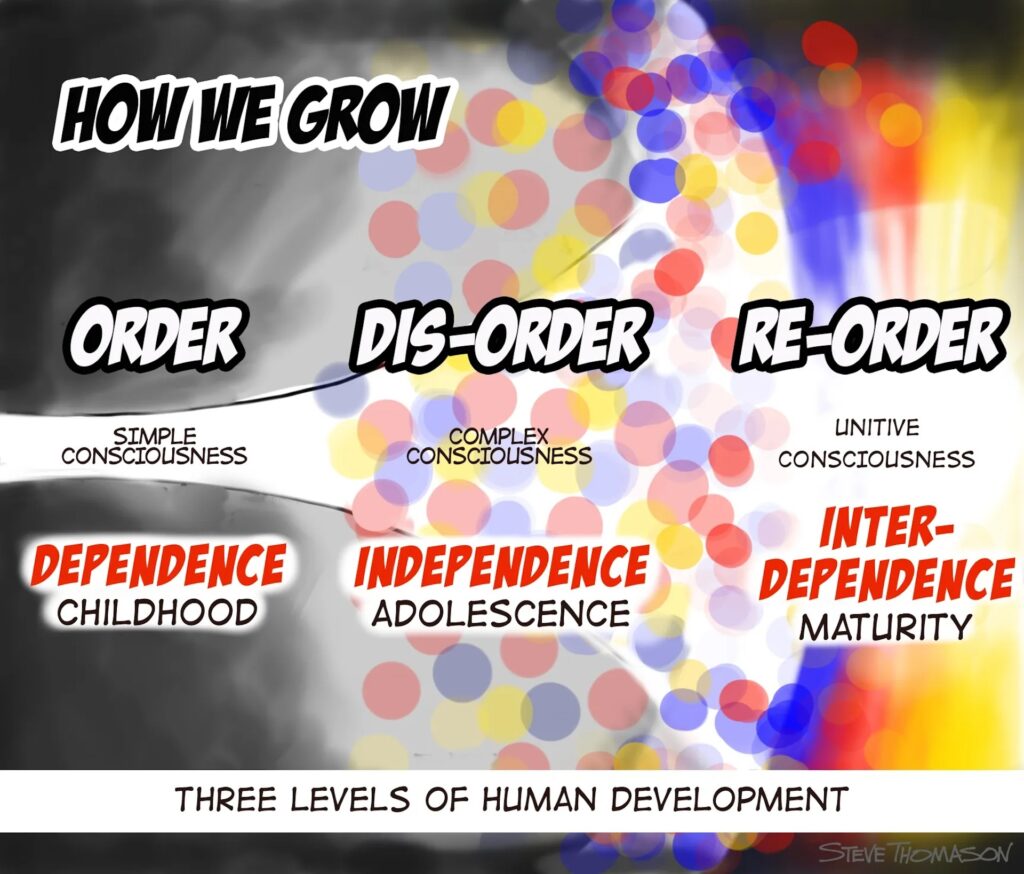

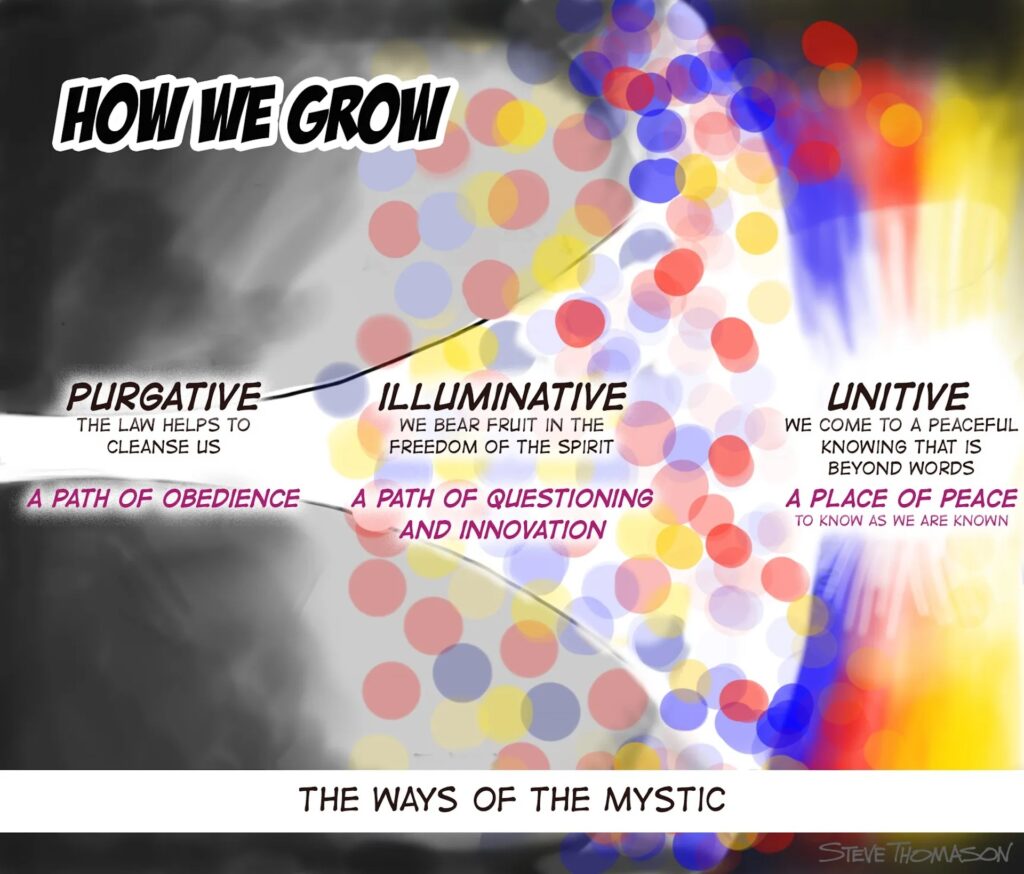

OK, here is one last set of images that will connect this to the process of spiritual formation. Father Richard Rohr talks about the three phases of the spiritual journey:

order

disorder

re-order.

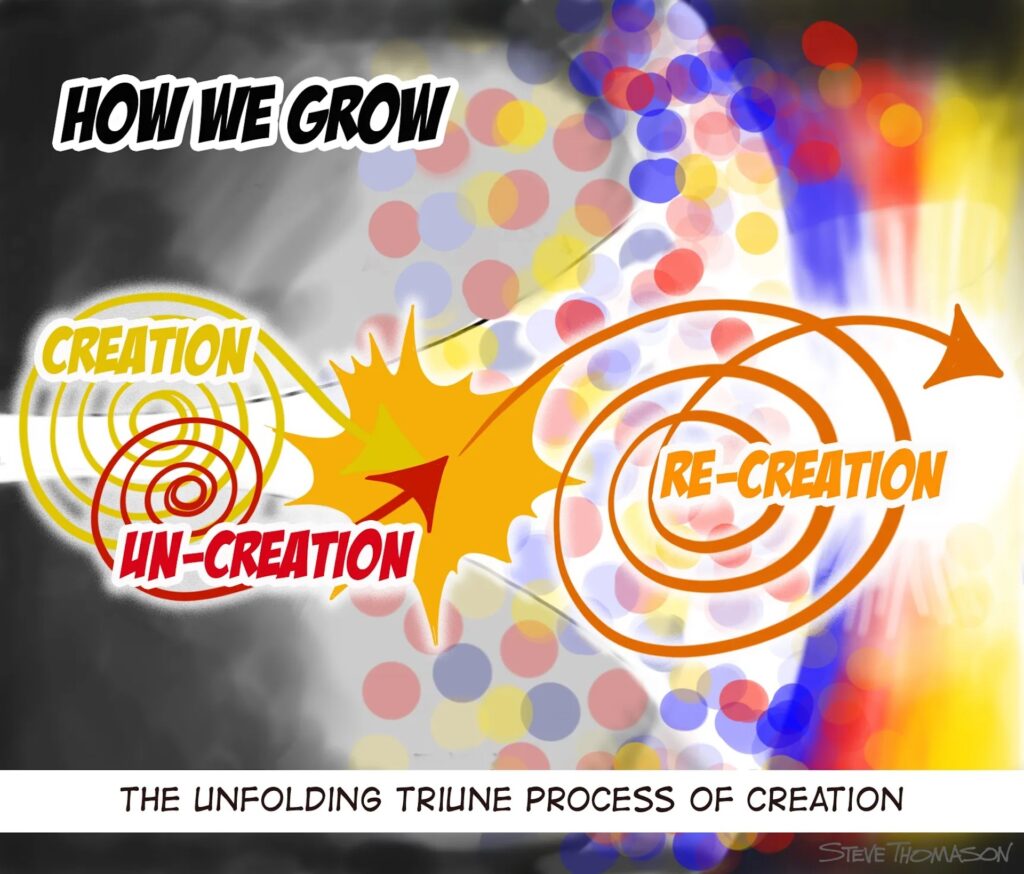

Walter Bruegemann names this cycle as

creation

uncreation

recreation.

It is the natural process of human development.

It is what the medieval mystics call the three-fold path.

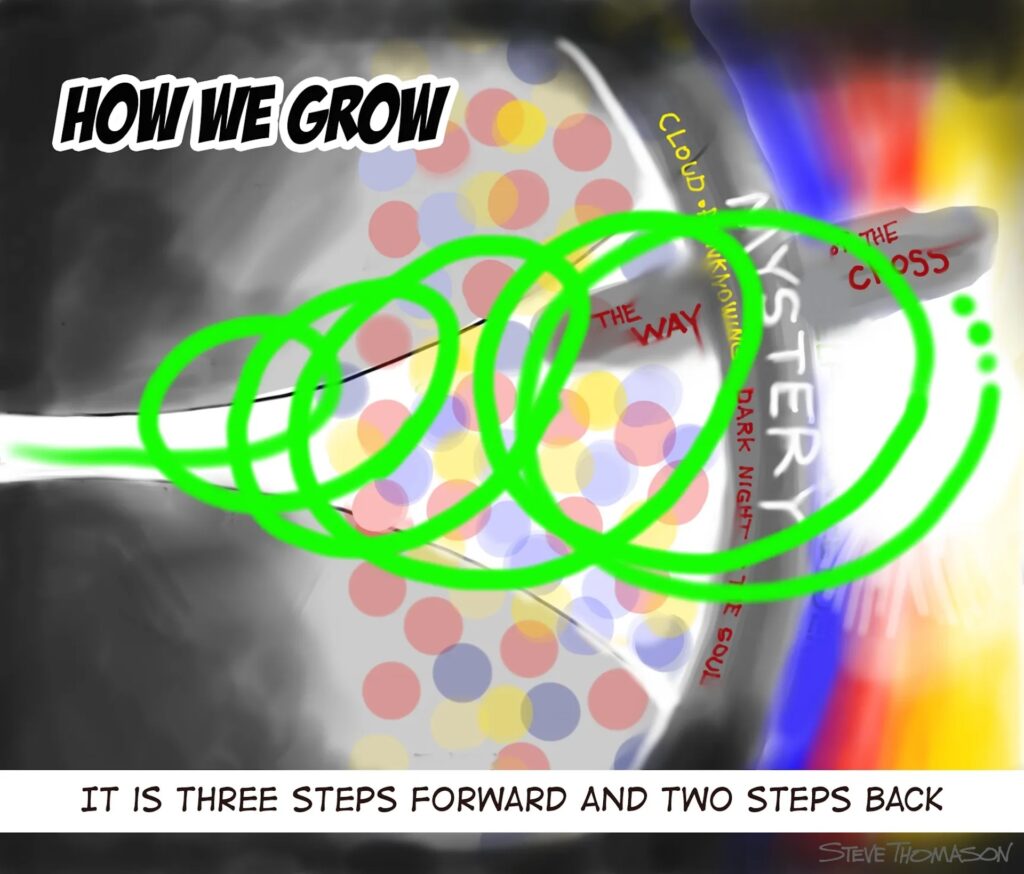

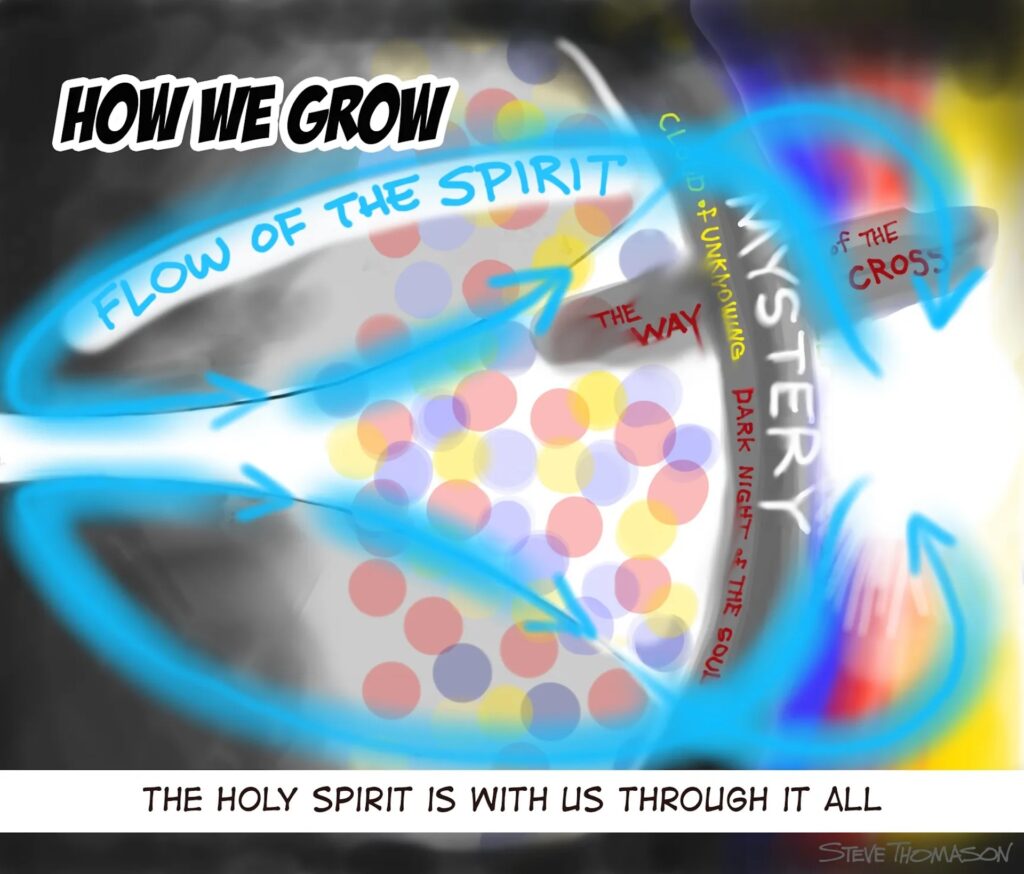

It is important to name that this is not a linear journey. Deconstruction is not a one-time event. It happens in layers and spirals. Once we think we have things worked out, another crack forms and we go back to a new level of deconstruction.

And, as a disciple of Jesus, I would name it as the way of the Spirit and the way of the cross. We live, we die, we are resurrected…rinse and repeat.

And this is my prayer of daily deconstruction. Kill me, Fill me, Spill Me.

Interested in more from Steve? Check out his website where this piece originally appeared, and his Faith+Lead Academy courses: Overflow: An Introduction to Growing in Faith and The Gospel of Matthew: Life in the Way of God.