Beginning at the end

On a spring afternoon in 1945, a young German pastor boarded a bus with his fellow prisoners for the final leg of their journey to the Flossenbürg concentration camp in the Bavarian mountains. Only hours later on the morning of April 9, he and the other conspirators were executed for their connection to a failed plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

The pastor was just 39 years old when he died. But his theology had already begun to transform the church and in the years that followed, his words would resonate far beyond the terrible circumstances of Nazi Germany. His ideas about the importance of personhood are especially relevant in our current landscape of deepening mistrust and polarization. Who was this resolute man of faith who made the ultimate sacrifice for what he believed? His name was Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and he has an urgent message for us today.

Discovering Dietrich

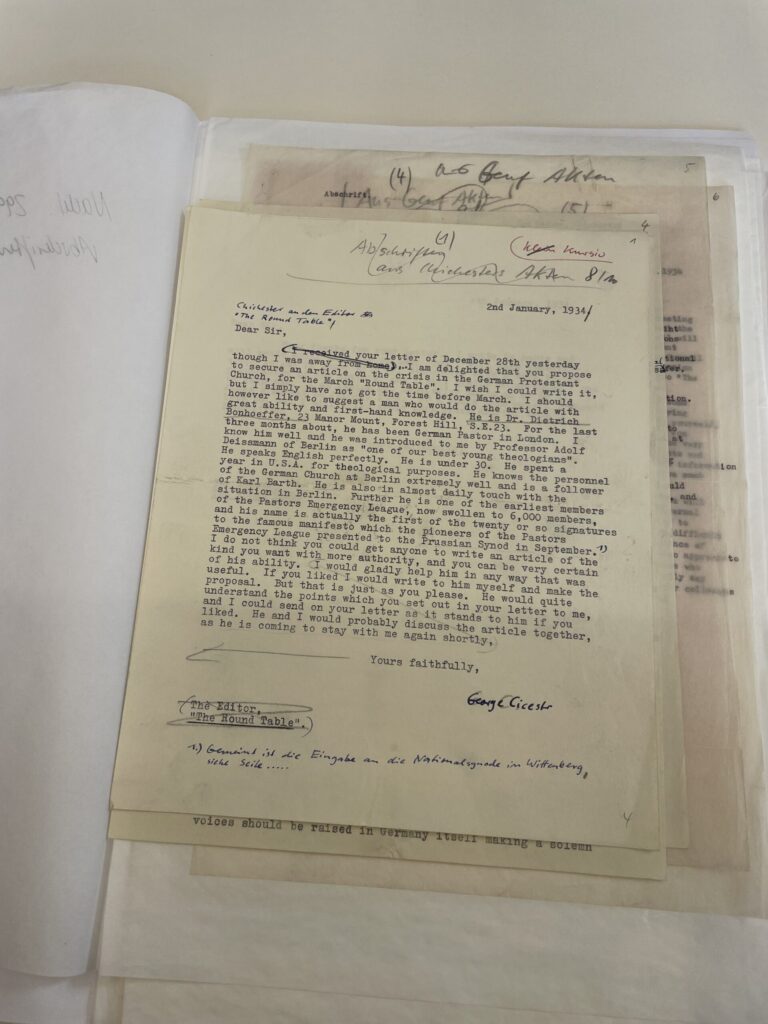

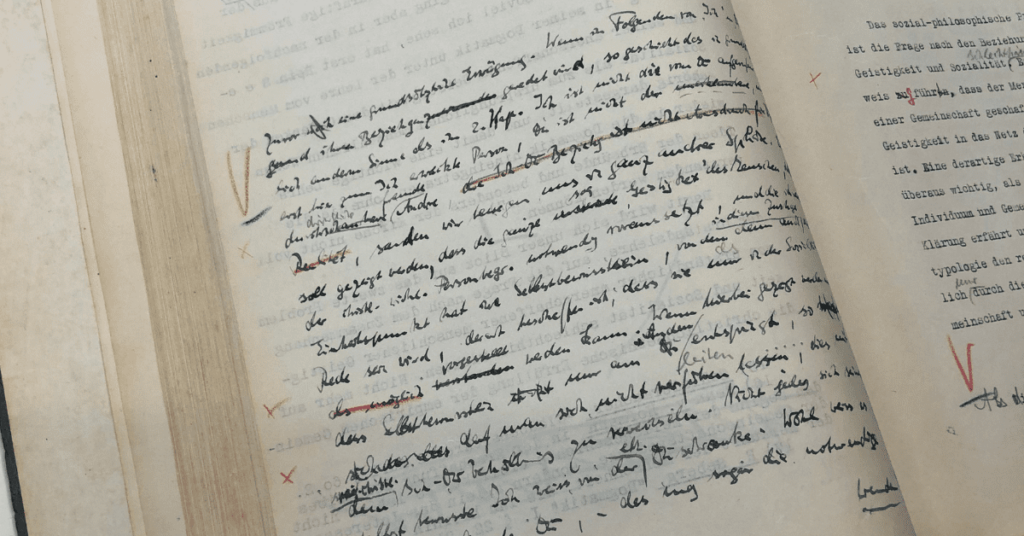

This summer I traveled to Berlin with Dr. Andy Root and several Luther Seminary colleagues, graduates, and students to see firsthand the places that shaped Bonhoeffer’s life and theology and better understand the importance of his story. Our trip included a visit to the Topography of Terror Museum to explore the rise of Nazism as well as to the German Resistance Memorial Center to learn about the people who fought against the horrors of the Third Reich. We also got the rare opportunity to handle Bonhoeffer’s original letters and documents from the collection at the Berlin State Library.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was born in 1906 into an elite family of wealth and privilege. He and his twin sister Sabine were the second youngest of eight children. His father Karl was the top psychiatrist in Berlin, and his mother Paula hailed from a long line of aristocrats, theologians, historians, and artists. All of the Bonhoeffers were highly educated. The family’s sons and sons-in-law held high-ranking positions that included physicist, lawyer, and judge. Only two of the young men would survive the war.

Unlike his siblings, Bonhoeffer chose to become a theologian. As a Lutheran scholar and pastor, he wrote prolifically, taught seminary courses, led confirmation classes, preached sermons, and even started his own illegal seminary when the state church turned away from the gospel and embraced Nazism.

Bonhoeffer traveled extensively in Europe and the United States, and his strong connections with church leaders abroad made him an ideal candidate to share information about the true state of affairs in Germany. This became his role as part of the failed assassination plot.

For example, Bonhoeffer developed an alliance with Bishop George Bell of Chichester in England. In a letter of introduction to the editor of the publication “The Round Table,” Bell repeats an earlier description of Bonhoeffer as “one of our best young theologians.” Bell wrote, “I do not think you could get anyone to write an article of the kind you want with more authority, and you can be very certain of his ability.” This glowing praise offers a small glimpse into how Bonhoeffer’s contemporaries saw him. He and Bell later became close friends, and some biographers agree that Bonhoeffer’s supposed last words included a personal message to Bell: ”[T]ell him that this is for me the end, but also the beginning.”

A changing world

Bonhoeffer lived through difficult times that began in his childhood. Like all Germans, the tragedies of World War I affected his family, too, as Dietrich’s older brother died from wounds he sustained in the fighting. The repercussions continued for the entire nation after the war as Germany saw its territory and power severely curtailed by the punitive Treaty of Versailles. The country suffered financial losses by being forced to pay exorbitant reparations to France and other Allies, plunging it into bankruptcy. Even with their wealth, the Bonhoeffer family struggled to keep food on the table. Germans everywhere wondered how they had managed to lose the war when their leaders had continually assured them of victory. Their trust in the government evaporated and anger rose in its place.

Into this vacuum of power stepped the cunning Adolf Hitler. He used his charisma to stop the payments to foreign governments and this action (among many others) revived Germany’s economy. The people were thrilled and, believing they deserved to triumph after so many losses, agreed to elevate Hitler to even higher levels of authority in spite of any misgivings they had about the rest of his agenda. They would come to learn in time how wrong they had been.

Nazi dehumanization

Much is known about the Nazi’s programs of systematic torture and death. But it’s important to consider where some of their ideas originated and why there wasn’t more public outcry against them.

Germany and its leaders were deeply influenced by the philosophy of Frederich Nietzsche. In World War I, German soldiers were given small printed editions of his novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra to carry with them into the field. Nietzsche originated the idea of the Übermenschen—heroic humans who claimed power and superiority over others, and who sought to eliminate the weak from among them for the good of society. The Nazis embraced this concept and took it further. It wasn’t enough to simply kill the enemy; undesirable people needed to suffer and internalize their unworthiness. The Third Reich waged the ultimate campaign of dehumanization.

In her Unlocking Us podcast, Dr. Brené Brown explains that dehumanizing others is the precursor to genocide. “There’s no empathy,” she says. “There’s no conflict resolution or conflict understanding. It’s just zero-sum… [the] new goals become ‘punish and destroy the opponent,’ and in some cases, more-militant leadership comes into power.”

This is an apt description of what the Nazis did. Our group saw evidence of the depth of their cruelty as we walked through the Sachsenhausen concentration camp where Bonhoeffer’s brother-in-law Hans was killed and where some of his colleagues were imprisoned.

Hundreds of thousands of camp inmates were used for forced labor, and some underwent unspeakable medical experiments. All were stripped of their humanity, unable to eat, sleep, or even clean themselves with any semblance of dignity.

Many Germans were aware of the atrocities taking place inside the camps scattered across the country. But they didn’t protest because they had been conditioned to see the prisoners as less than human. As Dr. Brown notes, “During the Holocaust, Nazis described Jews as Untermenschen, subhuman. They called Jews rats and depicted them as disease-carrying rodents in everything from military pamphlets to children’s books.” These language choices normalized brutal behavior. Other Germans saw the acts of depravity as necessary for their own survival. They wanted to protect themselves and their families from the hardship and starvation that occurred after World War I even if it meant the deaths of their neighbors.

Theology of personhood

Bonhoeffer vehemently opposed the Nazis’ barbarism. Events throughout his lifetime shaped his views, but some of his core ideas were present from the beginning. His first doctoral thesis—Sanctorum Communio or “the community of saints”—was finished in 1927 and published in 1930. In it he affirmed the value of personhood in ways that later were an antithesis to the values of the Third Reich.

The church community according to Bonhoeffer is the physical manifestation of Jesus Christ in the world. Christians are defined by their connection with God and with each other. Each human person has individual worth as God’s special creation, and each person is also bound to others within the community. As Bonhoeffer wrote, the mutuality and interdependence of these relationships is such that “the weaknesses, needs, and sins of my neighbor afflict me as if they were my own, in the same way as Christ was afflicted by our sins.”

Our human frailty is something to be celebrated, not abhorred, because through it we share in Christ’s suffering. Bonhoeffer preached a sermon in London during 1934 in which he expounded upon the extraordinary idea that God’s “power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9 NIV). He boldly named the contrast between the strategy of the newly appointed Hitler and the ways of God: “Against the new meaning which Christianity gave to the weak, against this glorification of weakness, there has always been the strong and indignant protest of an aristocratic philosophy of life which glorified strength and power and violence as the ultimate ideals of humanity.”

This grasp at power represents the false Übermenschen of the Nazi regime, and it is in direct conflict with God’s kingdom. In Psalm 82:3-4, the writer spells out what God desires for his people: “Give justice to the weak and the orphan; maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute. Rescue the weak and the needy; deliver them from the hand of the wicked” (NRSVue). There is no question that God sides with the marginalized and oppressed.

The choice before us

We are at a pivotal moment in history where our personal choices as well as the decisions of our nation’s leaders will either lead us closer to God’s reign or away from it. Will we repeat the mistakes of the past, or will we draw upon the rich wisdom of theologians like Bonhoeffer and follow the way of love—the way of Jesus? Will we choose to embrace our neighbors, especially those who are different from us?

Confession and acknowledgment are important practices for us in these challenging days. Berlin offers some guidance; despite its troubled history, the city deliberately pays tribute to its past. Small brass plaques dot the streets like golden tiles among the cobblestones, each one marking the location where a person once lived who was forcibly taken into custody and killed. The stones are inescapable for pedestrians—a constant visual reminder of what happened and also part of the current fabric of daily life.

The stones invite introspection and remembrance, as does the somber Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe near the Brandenburg Gate. The rows of concrete slabs create a disorienting experience that overwhelms the visitor, much like the horrors of the Holocaust are difficult to quantify.

These are cautionary tales of what can happen when we stop seeing each other as people—when we’re no longer able to love our neighbors. This is why Bonhoeffer’s words are so important for us today.

Encountering Bonhoeffer

The specter of Dietrich Bonhoeffer remained present with us throughout the trip. Our group spent extended time in the former Bonhoeffer home in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin. It was here, in the unassuming kitchen and in the quiet of the surrounding woodlands, that the family covertly discussed the details of the Hitler assassination conspiracy and considered how they and others might reclaim their beloved Germany from the Third Reich. The curators of the house have styled it today as a “place of encounter” where people can connect with Bonhoeffer’s legacy and reflect on what it means for us now.

I noticed that as the trip progressed, threads of Bonhoeffer’s story appeared in both expected and unexpected places. There were natural connections, of course, to the family’s house, to the churches where Dietrich preached and taught, and in the World War II museums and historical sites we visited. But one surprise occurrence was especially poignant.

We toured the Olympic Stadium where Black American athlete Jesse Owens broke records and won medals during Berlin’s 1936 summer games. We even stood in the formerly named “Führer Box” in the exact spot where Adolf Hitler looked on in rage as his carefully crafted narrative of Aryan superiority was effectively dismantled. It was a surreal and rather uncomfortable experience to occupy the same space.

As our group took a brief break, I chatted with the local German tour guide. He joked about being overworked by the stadium’s busy events schedule. We had coincidentally arrived in Berlin during the closing days of the international Special Olympics, and workers were still cleaning up from the previous night’s Pink concert.

The guide suddenly became serious, and his change of tone caught my attention. “You know what I like about the Special Olympics?” he asked me. It sounded almost like a confession, and I found myself leaning in expectantly. “It’s about people,” he said. “The athletes of the regular Olympics are like professional superstars,” he said, “but these athletes are human. They’re just people. And these games cultivate that.” I could hear the awe in his voice and see it reflected on his face.

Standing there in the stadium, with the quiet hum of work happening around us, I heard the echoes of Bonhoeffer. Our personhood matters, and God invites us to truly see one another as the complicated, messy, and beautiful creatures that we are. We must never lose that. Our faith, and the fate of this world, depend upon it.

Reflection questions

- What does God say is true about you? What does God say about your neighbor? Are those two things the same or are they different?

- How does your current cultural context help or harm the way you view other people?

- What is your responsibility to your neighbor? To your community? To the world?

- How might Bonhoeffer’s ideas about personhood help you to love others more deeply?

- When might God be encouraging you to take a stand on behalf of your neighbor?

Select Bibliography

- Charles Marsh, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Alfred A. Knopf (a division of Random House), 2014.

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Sanctorum Communio: A Theological Study of the Sociology of the Church. Translated from the original German edition by Reinhard Krauss and Nancy Lukens. Edited by Clifford J. Green. Found in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 1, Fortress Press, 1998.

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “My Strength Is Made Perfect in Weakness,” London, Evening Worship, 1934, undated, found in The Collected Sermons of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, edited by Isabel Best, Fortress Press, 2012.

Suggested resource for further study

You are invited to take the Faith+Lead Academy course Faith, Lies, and Spies: Bonhoeffer’s Life and You with Dr. Andy Root. This self-paced online offering will help you consider all of the ways God is at work. Explore Bonhoeffer’s story and complete a personalized timeline of God’s activity in your own life. Learn how spiritual practices helped Bonhoeffer prepare for the difficulties of God’s calling, and be encouraged to try some of them yourself.